Former Chief Justice to Congress: ‘Be peacemakers, peace builders’

By Luis Adrian A. Hidalgo

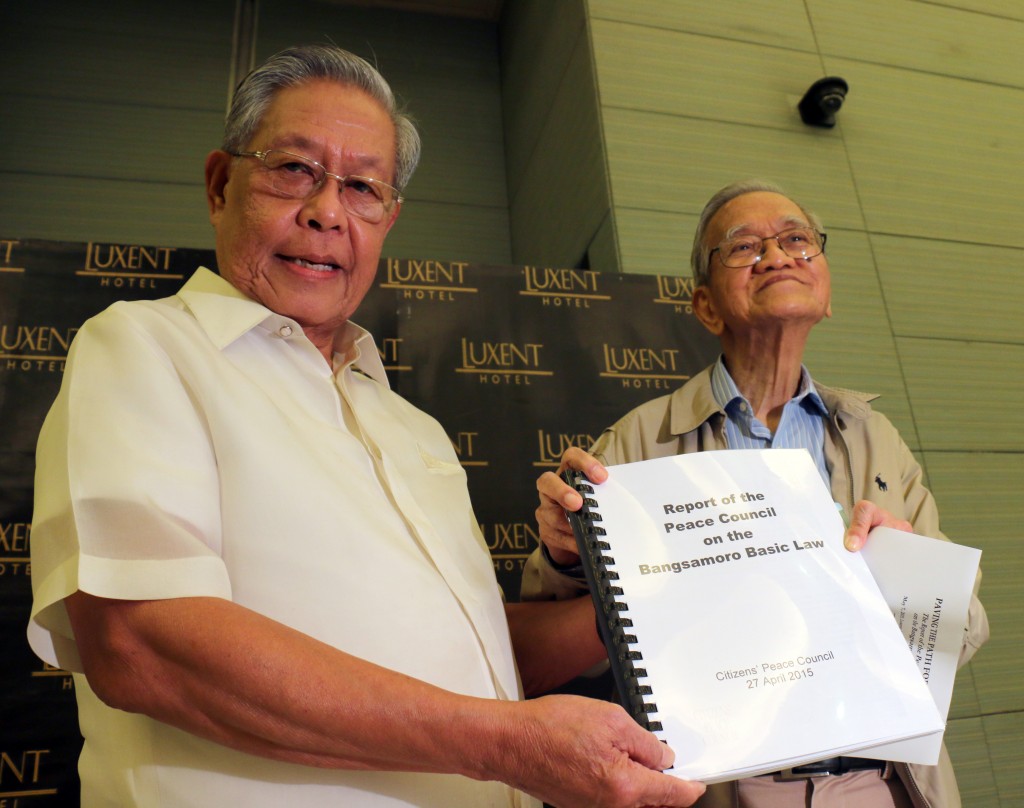

PEACE COUNCIL members former Chief Justice Hilario Davide and former Philippine Ambassador to the Holy See and Malta Howard Dee. Photo by Luis Adrian A. Hidalgo.

“BE PEACEMAKERS, peace builders, and peacekeepers.” Former Chief Justice Hilario Davide reiterated this message to lawmakers deliberating on the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL).

The BBL, he also told participants in the first public forum on the Peace Council’s findings on the draft law, is not in violation of the 1987 Constitution, but may require some tweaking.

The forum on May 7 at Luxent Hotel in Quezon City was facilitated by the Alternative Law Groups in partnership with Oxfam and was attended by indigenous peoples, NGOs and peace advocates.

With Davide as chair of the Constitutionality and Forms and Powers of Government Cluster, the Peace Council earlier presented its report on the draft Law to the House of Representatives and the Senate as Congress resumed discussions on the proposed law. (See sidebar)

|

Sidebar: Peace Council presents BBL report FOLLOWING THE call by President Aquino to respected citizen leaders to convene an independent group that will scrutinize the proposed Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the members of the Peace Council constituted themselves into clusters to identify and study potentially contentious issues in the draft law. The clusters are headed by former Chief Justice Hilario Davide Jr. (Constitutionality, Forms and Powers of Government Cluster), businessman Jaime Zobel de Ayala (Economy and Patrimony Cluster), Ambassador Howard Dee and Bai Rohaniza Sumndad-Usman (Social Justice and Human Development Cluster), and Retired General Alexander Aguirre and former Education Secretary Edilberto de Jesus (Human Security [Peace and Order] Cluster). The Peace Council presented its report before the House Ad Hoc Committee on the BBL lead by Congressman Rufus Rodriguez on April 27, and before the Senate Committee on Local Government headed by Senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. on May 5. The Council’s report was later presented in a public forum facilitated by the Alternative Law Groups in partnership with Oxfam at the Luxent Hotel in Timog Avenue, Quezon City on May 7. |

The Council is a private effort to expand discussion on the BBL to include civil society and other stakeholders. On March 27, 2015, President Benigno Aquino Jr. invited Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle, businessman Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala, founder of Teach Peace, Build Peace Movement Bai Rohaniza Sumndad-Usman, former Philippine Ambassador to the Holy See and Malta Howard Dee, and former Chief Justice Hilario Davide, Jr., to review the draft law.

Because of the disastrous SAF operation in Mamasapano in January which claimed at least 67 lives, the chairperson of the Senate Committee on Local Government, Senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. stopped deliberations on the draft.

Both the Senate and the House held hearings on the Mamasapano clash and on the extent of the involvement of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in it, with several lawmakers expressing doubts about the wisdom of passing the BBL.

Implementing the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro that the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the MILF signed on March 27, 2014, the BBL seeks to provide genuine autonomy for the Bangsamoro people and bring an end to the armed struggle of the MILF.

The Philippine government signed a peace agreement with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) on August 1, 1989 which resulted in the establishment of the Autonomous Region in Muslim (ARMM).

Acceptable and deserving of support

The presentations of the Peace Council opened the public debate on the BBL to different perspectives. Before the Peace Council released its findings, opponents of the bill had dominated the sources cited in 94 news reports and segments. (See “Coverage of the BBL [7-14 April 2015]: Bias and Prejudice against Bangsamoro“) The Councils’ detailed detailed explanations of the BBL provisions attracted news attention and shifted the focus of the coverage from being mostly negative to a more constructive discussion of the proposed law.

Davide and framers of the 1987 Constitution took exception to some critics’ claim that the draft law is constitutionally infirm. The Council recommended changes in terminology to address the concerns of those who feel that its provisions encroach on the powers of national government and threaten national sovereignty.

The Council report said the draft law “deserves the support of all Filipinos,” and that it “complies with the Constitution’s mandate for the creation of autonomous regions, within the framework of the Constitution and the national sovereignty, as well as (the) territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines.”

But the Peace Council also acknowledged that the draft law is not perfect, and presented recommendations for refining some of its provisions.

Most of the contentious issues identified by the report either require changes in wording, or more detailed explanation, or a definition of certain terms to clarify meaning and prevent misinterpretation.

Optimism for the BBL

Those present at the meeting expressed optimism about the prospects of the BBL. “I don’t really see anything bad about the BBL. . . I congratulate my Christian majority friends, brothers and sisters, for being in the forefront of promoting the rights of everyone in this country, particularly the Bangsamoro,” said a member of the Young Moro Professionals Network. “I urge my compatriots, my countrymen, to support the BBL,” she said.

A man who identified himself as a member of the Teruray tribe in the Bangsamoro core territory also expressed support for the draft law, calling the BBL a “golden opportunity.”

“For us indigenous peoples, most especially those in the Bangsamoro core territory, we fully support the BBL because we think that it is the solution for our aspirations,” he said in Filipino, as he called for the passage of the BBL, with all the provisions for the indigenous peoples kept intact.

Rights of Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples in the BBL

The open forum also allowed other participants to raise concerns about how well the BBL addressed problems regarding non-Moro indigenous communities affected by the BBL. Francis Dee, executive assistant to Ambassador Howard Dee, pointed out that tribal leaders were invited to the deliberations of the Cluster on Social Justice whose members were one in their desire for the BBL to assure that their rights under the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA-RA 8371) and other laws are “reasserted, recognized, and protected.”

For this reason, the Cluster suggested that a separate article be devoted to the recognition, protection, and promotion of non-Moro indigenous people’s rights, as stated in the IPRA, until more appropriate solutions are made by the Bangsamoro Parliament. Dee also said that the Cluster is recommending that a more comprehensive enumeration of non-Moro indigenous people’s rights be included in the BBL.

To address expressed concerns about land reform and land rights, Dee said that the classification and allocation or assignment of land titles will be devolved to the Bangsamoro Government as it currently is in the ARMM.

However, former Education Secretary Edilberto de Jesus, co-chair of the Human Security (Peace and Order) Cluster, noted that there will be problems with regards to land as in the Lumad community, “land is a communal resource.”

“When we try to implement a framework that gives the asset to individual owners, we have a problem,” he said, noting how property is regarded by lumad communities.

Dee said that the Council leaves the decision on how the issue would be addressed to Congress. He reiterated, however, that the Cluster agrees that it is important to hear the indigenous peoples’ voices on the matter.

Representation and participation

ALG national coordinator and lawyer Marlon J. Manuel, in response to a suggestion to conduct more discussion sessions, said the group will be doing similar programs and will be disseminating information about the report.

“The first part (presentation of findings) is being translated at this time to Binisaya, Mindanawon, Tagalog, and other languages, hopefully,” Manuel said.

The Social Justice and Human Development Cluster’s report noted that “the BBL is replete with references to social justice,” leading to the conclusion that social justice is the framework of the draft law.

“The BBL is a social justice issue,” Dee said. “It’s a social justice issue because all of the historical injustices are yet to be rectified.”

For example, Article IV, Section 7 asserted that social justice “shall be promoted in all phases of development and facets of life within the Bangsamoro.” Meanwhile, Article XIII, Section 1 states that the Bangsamoro Government’s economic policies and programs “shall be based on the principle of social justice.”

Dee said the Cluster’s recommendations are mostly refinements of the BBL. The report recommended that the terms “Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples,” and “Fusaka Inged,” among others, be defined in the BBL. The Cluster also recommended an article be added to define social justice in accordance with the Philippine Constitution, and an additional section dedicated to the poorest of the poor with regards to attaining social justice.

The Cluster also recommended Peace Education as an integral part of the education to be adopted in the region, along with topics like Bangsamoro history, culture, and identity, to eliminate prejudice and marginalization towards the Bangsamoro people.

Expanded number of reserved seats

|

Bai Rohaniza Sumndad-Usman delivered the concluding remarks of the Peace Council’s report at the April 27 Congressional hearing on the Bangsamoro Basic Law. Read the speech here: “On the path to lasting peace in Mindanao“ |

Responding to a comment that more seats should be allotted to the women’s sector in the envisioned Bangsamoro Government, Manuel noted that the Social Justice and Human Development Cluster did recommend expanding of the number of seats for marginalized sectors as provided in Article VII, Section 5 (3) of the BBL to be allotted to the youth, women’s, and indigenous peoples’ sectors.

“The refinement is to increase the number of seats that should be reserved to women and indigenous peoples,” Manuel said, adding that it is “one of the different arenas for the struggle for gender equality.”

Addressing violence

A question was also raised regarding how the current gun law (Republic Act 10591), which allows an individual to carry at least fifteen firearms, would factor in the decommissioning process of the MILF.

Referring to a study by International Alert, a member of the said organization cited one of the main findings that “violence in the Bangsamoro is due to the immediate access to illicit weapons.”

De Jesus said, however, that although there are many sources of violence in Mindanao, there are more incidents arising from clan feuds, the shadow economy, and rebellion-inspired incidents.

“The biggest sources of damage, however, are rebellion-inspired incidents. There are fewer of them, but when they happen, they immediately lead to massive displacement of communities, refugees, and also many more lives lost,” he said.

He also noted that it is the state of lawlessness that breeds violence. Add to that the presence of many armed groups that complicate the decommissioning process. This, he said, is another reason why the MILF does not want to surrender its firearms, until it is assured of greater political stability in the region.

“It’s not afraid of the government. They’re afraid of the BIFF (Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters), they’re afraid of the drug dealers, the kidnap for ransom syndicates. There are other threats for which they feel the need to keep their firearms,” he said.

A necessary first step to start anew

A historic undertaking, the BBL is no ordinary legislation. As the Peace Council’s report said, it is “an instrument to pursue social justice and development,” not just for the constituents of the envisioned autonomous region and for the entire Mindanao, but also for the country in general.

The Council acknowledged that there are larger governance and justice issues not only in the autonomous region or in Mindanao, but in the entire country as a whole. And these issues must be addressed beyond the BBL.

The draft Bangsamoro Basic Law is the fruit of no less than 17 years of negotiations by peacemakers from both sides of the table, beginning with the forging of agreements in 1997, the signing of the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro on October 15, 2012, to the signing of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. To set aside these milestones, as the Council said, “would be imprudent and wasteful.”

The Peace Council concluded their report by affirming that the BBL is a path to peace. It will not solve all problems of the country or of the envisioned autonomous region, the Council said, but it is “a foundational element” and “a necessary first step” for a new beginning “to correct the mistakes of the past,” and “to craft a better future.”

In the interest of transparency and full disclosure:

Former Education Secretary Edilberto de Jesus is the husband of CMFR Executive Director Melinda Quintos de Jesus, and Secretary Teresita Quintos Deles, Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process, is her sister. The space given to Peace Journalism, however, is part of the long term program agenda CMFR has been observing since the early 1990s.

Leave a Reply