Was Media to Blame for the “Muddle in Manila”?

THE OPENING of the 2019 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games followed days of embarrassment for its organizers as headlines around the world highlighted the lack of planning and plain incompetence in the handling of arrivals and addressing the needs of participants.

Tagged by foreign media as the “Muddle in Manila,” the reports called attention to logistical blunders, unfinished game venues, inadequate meals, and dismayed delegates. The organizers were hounded by Filipino netizens who took to social media to criticize their gargantuan budget but dismal performance of the Philippine Southeast Asian Games Organizing Committee (PHISGOC).

But government and PHISGOC officials, along with their supporters in social media blamed the local press for allegedly exaggerating the “isolated” mishaps just to put the organizers in a bad light.

PHISGOC Chief Operating Officer (COO) Ramon Suzara slammed the media for their supposedly “negative reporting.” In a press conference, he urged the media to focus on “the positives” to help ensure the country’s successful staging of the region’s premier sporting meet.

Kabayan Party-list Rep. Ron Salo, chair of the House Committee on Public Information, pushed for a probe into the alleged spread of “fake news” surrounding the country’s hosting of the games. Salo called out the “concerted, deliberate, organized and seemingly malicious disinformation campaign in the media” to discredit the organizers. Expressing his support for the investigation, PHISGOC Chair and House Speaker Alan Peter Cayetano argued that the alleged disinformation was driven by certain groups who wanted to sabotage the country’s hosting for their “political” motives.

CMFR’s quick review of the coverage showed up a media narrative heavily dominated by the organizers and their government chorus groups. In reporting the preparatory period and the opening event, media mostly cited PHISGOC and government sources, among them the Philippine Sports Commission (PSC) and other agencies involved. In the preparatory phase, the “negative” accounts were outweighed by positive and neutral reports. With the start of the games proper, the sports events captured almost half of the coverage with little reference to the organizers.

CMFR conducted content analysis to check the veracity of the claims that the media were out to mislead the public with negative stories.

Its review of the coverage of the three major daily broadsheets (Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star and Manila Bulletin), as well as four primetime newscasts from the major networks (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, CNN Philippines’ News Night, GMA-7’s 24 Oras and TV5’s Aksyon) showed the PHISGOC’s claims to be false and without basis.

CMFR’s analysis includes the following themes: the debate on the PHP55 million cauldron, complaints about food and accommodations and other reported blunders. The time frame started with the period of preparations up to the opening ceremonies: November 11 to November 30, 2019.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Number of reports

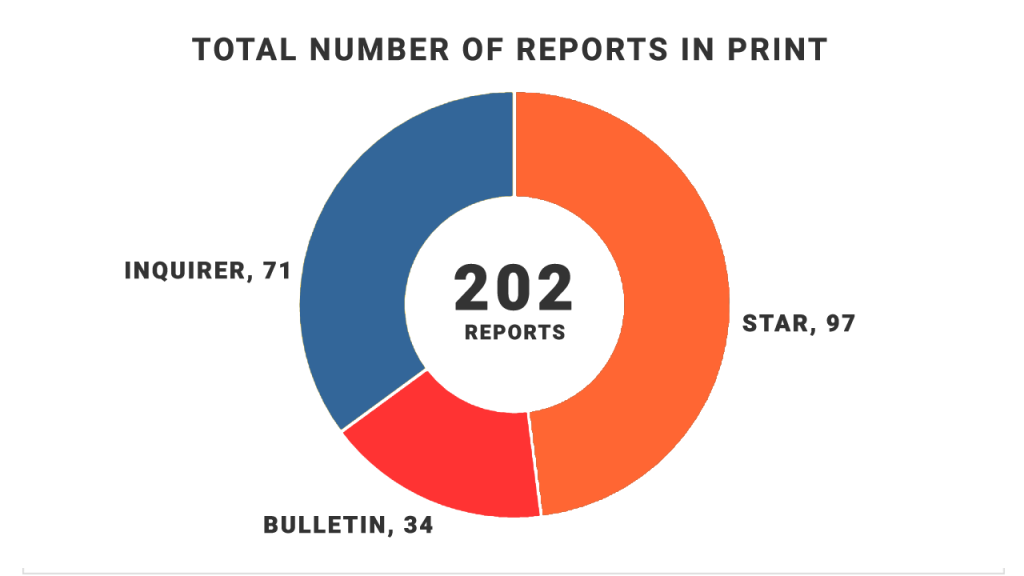

The three monitored broadsheets published a total of 202 reports. The Star had 97, 24 of which appeared in the news section, 73 in the sports section; the Inquirer had 71 reports, with 27 in the news section, 44 in the sports section; the Bulletin with 34, 11 in the news section, 23 in the sports section.

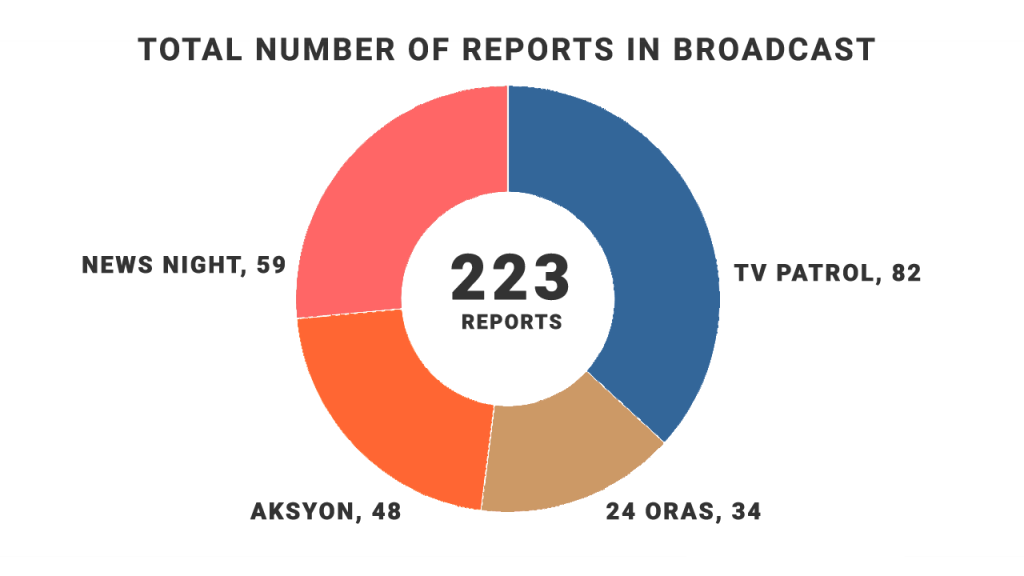

The four monitored newscasts aired a total of 223 reports. TV Patrol aired 82 news reports; News Night aired 59; Aksyon, 48; and, 24 Oras, 34.

QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

Subjects

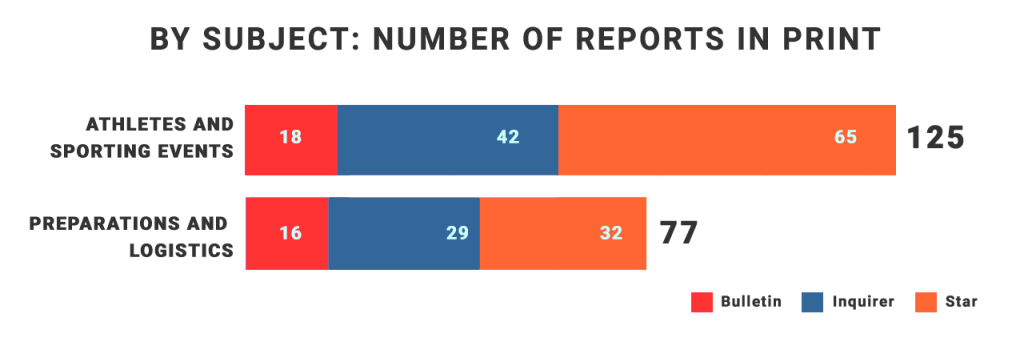

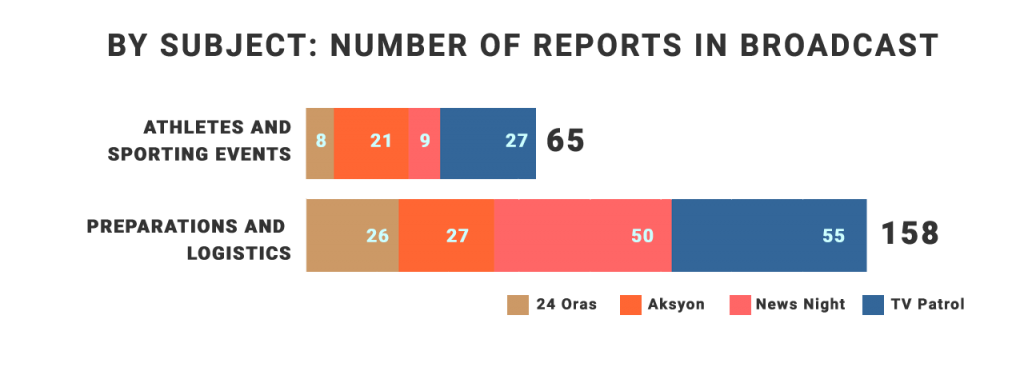

CMFR classified reports into two categories: (1) athletes and sporting events; and (2) preparation and logistics. The reports on preparation included coverage of the issues on the budget, security, media accreditation, and statements from organizing bodies and other concerned agencies.

In print, the reports on athletes and sporting events outnumbered those on the preparation and logistics. It should be noted, however, that the coverage on the athletes and games was mostly limited to the sports sections of the newspapers.

The opposite was observed in broadcast which more closely followed the narratives of both the organizers and their critics. News on preparations and organizing grossly outnumbered sports reports.

Sources

Most of the SEA Games reports depended on PHISGOC and government sources.

The top sources in print were from Congress, the Palace, PHISGOC, a national sports association and concerned agencies such as the PSC and the Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA).

| Alan Peter Cayetano (PHISGOC) | 20 |

| Salvador Panelo (Palace) | 17 |

| Rodrigo Duterte (Palace) | 12 |

| Franklin Drilon (Senate) | 11 |

| Mikee Romero (Congress) | 10 |

| Ramon Suzara (PHISGOC) | 10 |

| Bong Go (Senate) | 9 |

| Al Panlilio (SBP) | 6 |

| Butch Ramirez (PSC) | 5 |

| Vivencio Dizon (BCDA) | 5 |

The top TV sources were from PHISGOC, the Senate, the Palace, the Philippine National Police (PNP), as well as concerned agencies like the MMDA and the BCDA.

| Alan Peter Cayetano (PHISGOC) | 25 |

| Frank Drilon (Senate) | 17 |

| Salvador Panelo (Palace) | 14 |

| Ramon Suzara (PHISGOC) | 13 |

| Vivencio Dizon (BCDA) | 7 |

| Bernard Banac (PNP) | 5 |

| Bong Go (Senate) | 5 |

| Bruce Lim (SEA Games Executive Chef) | 4 |

| Butch Ramirez (PSC) | 4 |

| Vicente Sotto III (Senate) | 4 |

| Bong Nebrija (MMDA) | 3 |

| Celine Pialago (MMDA) | 3 |

| Chris Tiu (Director, SEA Games Volunteer Program) | 3 |

| Let Dimzon (Coach, Malditas Football Team) | 3 |

Slant for or against PHISGOC/administration

CMFR identified the slant of reports on preparation and logistics based on headline, content, placement, sourcing and word choice or tone.

In this context, positive reports focused on the success of the SEA Games and the organizers’ rebuttal to critics. Negative reports highlighted critical quotes, such as the “bloated” budget and other descriptions of blunders surrounding the games. These were often supported by evidence such as photographs. Reports were classified as neutral when it carried a fairly balanced perspective and words used were free of slant, straightforward as when news announce traffic re-routing or schemes and class cancellations.

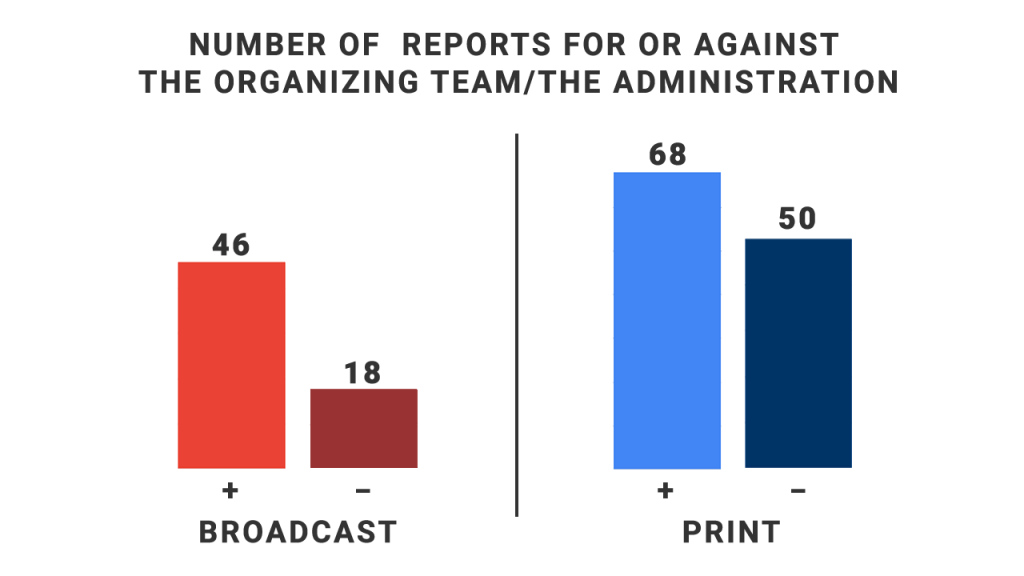

In print, 46 reports were considered positive, 18 negative and 13 neutral.

In broadcast, 68 reports were considered positive, 50 negative and 40 neutral.

Role of the press

Media began reporting on the games as soon as officials made announcements about their preparations. These were straightforward accounts. This was pretty much the style of the reportage even in reporting the mishaps.

Dedicated coverage of the SEA Games preparations was necessary to keep the public updated about their overall progress, as well as any backlog. Calling attention to organizational slips and snafus should prompt those concerned to improve on the delivery of services that Filipino athletes and our foreign guests require and deserve.

Fault-finding, even demonizing the media for their coverage of the SEA Games reveals an intolerance for criticism that is destructive to the practice of a free press. It is an attack on press freedom, because it suggests that any review or investigation of the conduct of government is necessarily partisan.

But this content analysis shows that the press was not excessive. In fact, it could be observed as having been somewhat restrained in its observation of PHISGOC’s faults and failures it has seemingly forgotten—or is not aware of — the role of the press to hold authorities to account through factual reporting. CMFR cheers journalists who stood by the truth, refusing to yield to the government’s attempt to reduce the role of journalists to mere public relations.

Leave a Reply