Sentiment and Science Against Labelling Children as Criminals

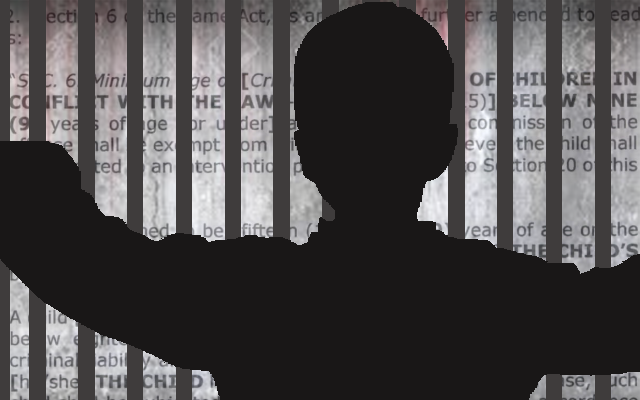

THE BROUHAHA over the lowering of the age of criminality — to nine, then twelve — reflected both science and sentiment about the issue which media picked up quickly as professional groups and human rights advocates protested against the idea.

That children can be in conflict with the law is a reality in the Philippines as it is in many countries. It has not been entirely ignored by Filipino lawmakers who passed the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act (JJWA) in 2006 to address the issue.

President Rodrigo Duterte, in his typical manner of simplifying complex problems, pushed for the lowering of the criminal age from 15 to nine as part of his anti-crime agenda. He said that children younger than 15 are getting bolder in committing crime because the law allows them to get away with it.

Voting on January 28, the House of Representatives passed on third and final reading House Bill (HB) 8858 lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) from 15 to 12. HB 8858 is a consolidation of six measures that would amend the JJWA to effect a lower MACR. Originally targeting a minimum age of 9, these proposals were all filed in Congress in 2016. The Senate recently held deliberations on its counterpart bills, proposing 12 as the MACR.

Supporters of these bills claim that these protect children from being used in organized crime. But human rights advocates and child welfare groups decry the punitive aspects of the measure.

Media coverage of the issue focused on the debate among lawmakers, civil society and government agencies.

CMFR monitored the reporting of three broadsheets (Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star, Manila Bulletin), four primetime programs (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, GMA-7’s 24 Oras, TV5’s Aksyon and CNN Philippines’News Night), and selected online news sites from January 21 to 29.

Data on Youth Offenders

There is more than enough scientific data on children’s cognitive development in relation to juvenile delinquency, much of which is accessible online. Social workers and scientists, health professionals and concerned organizations were quick to issue statements and position papers citing research-based evidence that proves that lowering the MACR does not deter crime. News reports picked up these statements from social media accounts of the critical groups.

Reports cited police figures that minors commit less than 2% of the total number of crimes, rejecting the premise of the bill. Supporting this data, Senior Supt. Angela Rejano of the PNP’s Women and Children Protection Center told CNN Philippines in a televised interview that the number of crimes committed by minors also decreased by 21% in 2017.

Government agencies such as the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council (JJWC) identified lapses in the implementation of the current law, including the shortage of and the dismal conditions of child care institutions, called “Bahay Pag-asa” – as provided for by the existing law. The CHR presented numbers in a forum that they held, while the JJWC was invited to speak in the Senate hearing last January 22.

These events, including a second Senate probe on January 25, were all covered by the media.

Diverse Views and Voices

Television and online reports included critical voices, engaging sources from civil society organizations to provide much needed information. News accounts on print focused more on politicians and government officials supporting the bill. Editorials and opinion pieces, however, sided with the experts and criticized the legislators’ disregard for science and misguided comparison with other countries that have lower MACRs.

Media showed up the lack of expert reference in the discourse among politicians. When legislators do invite outside experts, those who have studied the issue, they are hardly given sufficient time to expound on the subject and are often greeted with hostility when their views oppose those of their interrogators. The Senate did invite resource persons who all pointed to the weak implementation of the existing JJWA. Live coverage recorded the hostility of some politicians against their invited guests, which was duly noted by some media reports.

A TV Patrol report said in the course of the hearing, that Senator Richard Gordon who chaired the committee hearing, was “irritated” by the arguments that opposed the bill. The Inquirer reported that even though Gordon admitted to poor law enforcement, he was firm in his recommendation to lower the MACR to 12 “despite the lack of empirical evidence to justify it.”

During the Senate hearing, law enforcers present agreed that the existing juvenile law had not been implemented well, but they still insisted on the lowering of MACR. Media in general failed to probe the basis of this view. With so much coverage of the issue, some reports were still oblivious to the politics at work in the campaign to lower MACR, which was obviously just following President Duterte’s prescription to address criminality.

House Speaker Gloria Macapagal Arroyo said she supported the bill “because the President (Duterte) wants it.” Senator Gordon was not quite as candid when he said that he was in favor of lowering the MACR to 12 because “kursunada ko” (that’s what he preferred.)

These revealing statements were captured by reporters doing ambush interviews in Congress and were quoted in online news and primetime reports.

But only a few of these accounts noted how Arroyo and Gordon changed tunes. VERA Files pointed out that Arroyo has abandoned her original stand as president in 2006, when she signed the law setting the MACR at 15. News Night alone reported that Gordon voted on the same MACR when he was senator in 2006.

Such congressional pandering to the wishes of the president is another story in itself which media have yet to report. Some journalists should recall the chain of evidence to prove how this Congress has served as the president’s rubber stamp since 2016.

Leave a Reply