On Point: Media’s Quick and Intelligent Response to Duterte’s Writ Idea

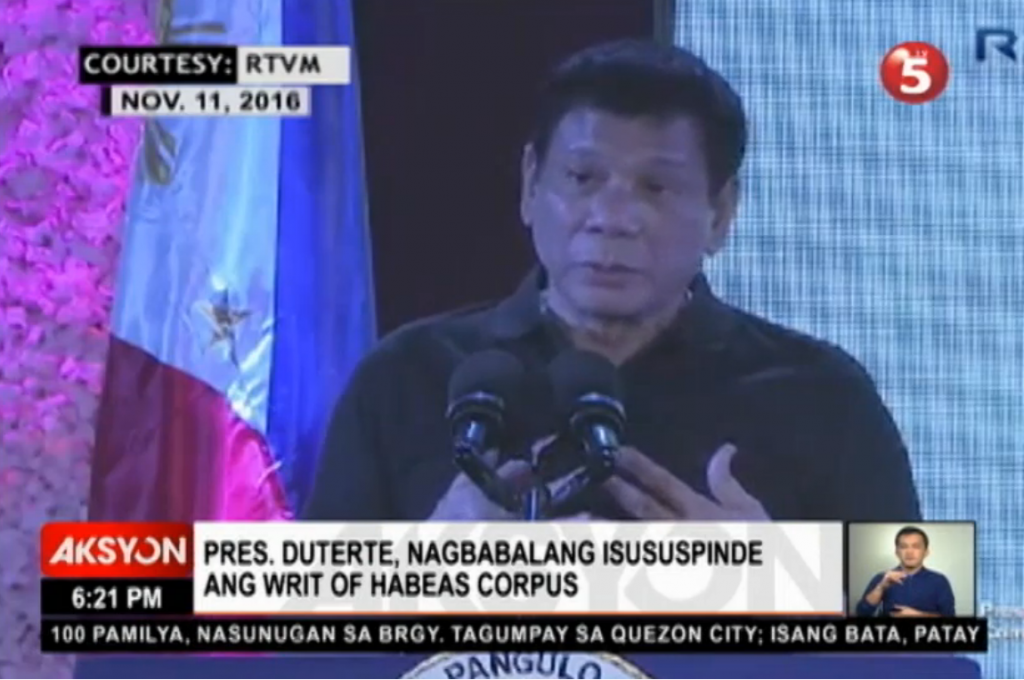

Screengrab from News5.com

CITING THE country’s problem with illegal drugs and rebellion in Mindanao, President Rodrigo Duterte said he may consider suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. Speaking during the launch of the Pilipinong May Puso Foundation on Nov. 11, the announcement drew the usual mix of reactions from officials, from lawmakers and legal experts.

Thankfully, the media quickly provided the necessary context and information to explain what Duterte’s proposal is about and what it would mean for the country and its citizens.

CMFR monitored reports from the newspapers Manila Bulletin, the Philippine Daily Inquirer and The Philippine Star, news programs 24 Oras (GMA-7), Aksyon (TV5), Network News (CNN Philippines) and TV Patrol (ABS-CBN 2), as well as relevant news websites from Nov. 12 to 15, 2016.

Explaining the Writ

Media coverage sufficiently explained the writ of habeas corpus—what it is, what it is for, the requirements for its suspension, and what happens if such a suspension is carried out.

Writ of Habeas Corpus A petition for the speedy release by judicial decree of persons who are illegally restrained of their liberty or to release them in favor of those who are entitled to their custody. – Cafuguan v. Cafuguan, SP-03894, Nov. 28, 1984 (Philippine Law Dictionary Third Edition, 2007, p. 1014) |

To determine whether an arrest or detention is legal, the court can order the presentation of the body, or the person. As put simply by the media, the writ of habeas corpus is a legal recourse that protects citizens from unlawful arrests and detentions.

Reports referred to the 1987 Philippine Constitution, particularly the provisions pertaining to the writ of habeas corpus (Article III, Section 15 and Article VII, Section 18). Under the Constitution, the president can suspend the privilege of the writ only in cases of invasion or rebellion when public safety requires it. The media noted that the suspension, however, can be questioned before the Supreme Court while Congress can either extend or revoke it through a joint congressional majority vote.

The Inquirer recalled the instances in the past when the writ was suspended: Elpidio Quirino on Oct. 22, 1950, responding to the threat of the communist rebel group Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon (Hukbalahap) and Ferdinand Marcos on Aug. 21, 1971 after the Plaza Miranda Bombing in Manila. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo on Dec. 4, 2009 ordered a state of martial law in some areas of Maguindanao after the massacre of 58 civilians in Ampatuan town of the same province (“In the know: Suspension of writ of habeas corpus,” Nov. 13, 2016)

TV5’s Aksyon Tonite (Nov. 14) supplied a meaty discussion of the writ of habeas corpus in a live interview with the president of the National Union of People’s Lawyers of the Philippines (NUPL) Atty. Edre Olalia by news anchor Ed Lingao. Among the points discussed by Olalia was the writ’s purpose, the conditions needed for its suspension, and the country’s past experiences with the writ’s suspension, particularly during the Martial Law period when many activists disappeared. Olalia also took exception to Chief Presidential Legal Counsel Salvador Panelo’s comment that the suspension of writ was an effective measure against crime and rebellion during Martial Law. While it might be effective, Olalia pointed out that it is repressive and leads to human rights violations.

PhilStar.com’s report argued that the writ prevents violation of human rights as law enforcement officers carry out arrests and detention and recalled the experiences of martial law survivor and Campaign against the Return of the Marcoses to Malacañang (CARMMA) spokesperson Bonifacio Ilagan and his companions who were also activists. (“Explainer: Why is the writ of habeas corpus important?” Nov. 15, 2016)

On Rebellion in Mindanao

In floating the idea of suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, President Rodrigo Duterte cited rebellion in Mindanao as one of his reasons.

Article III, Section 15 of the Constitution states that the writ “shall not be suspended except in cases of invasion or rebellion when the public safety requires it.” In a 24 Oras report, former University of the Philippines College of Law Dean Dr. Pacifico Agabin said that he did not think there is any threat of invasion or rebellion (“Atty. Agabin, walang nakikitang basehan para suspindihin ang pribilehiyo sa writ of habeas corpus,” Nov. 14, 2016).

De La Salle University College of Law Dean Jose Manuel Diokno in a TV Patrol report echoed Agabin but took exception to Duterte’s claims of rebellion in Mindanao, noting that the government seems to be equating criminality with rebellion. Diokno defined rebellion as a public uprising, an act of arms against government. (“Atty. Diokno: Writ of Habeas Corpus pwede lang suspendihin kapag may ‘invasion’ o ‘rebellion,’” Nov. 13, 2016).

Atty. Benedicto Bacani, director of the Cotabato-based Institute for Autonomy and Governance, said suspending the writ is an “extraordinary measure” that must be carefully considered. Bacani argued that it may not be beneficial to the peace process already set in motion and that it may reopen the “feeling of injustice” many in Mindanao have.

As for problem areas such as the Lanao and Sulu provinces—places where the Maute group and Abu Sayyaf operate, respectively—Bacani stressed in an interview conducted by Ed Lingao in Aksyon Tonite on Nov. 14 that what’s needed is law enforcement and the effective implementation of the peace process.

Different Voices, Different Opinions

The media recorded different opinions of concerned sectors and lawmakers on Duterte’s proposal. Those who questioned the idea included government officials: Vice President Leni Robredo, Senators Bam Aquino, Leila de Lima, Franklin Drilon, and Francis Pangilinan; Congressman Edcel Lagman.

Media prominently featured the differing statements from Malacañang and Duterte’s Cabinet. Along with Panelo, media also quoted Communications Secretary Martin Andanar who dismissed Duterte’s announcement as “just an idea;” and Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre, who said Duterte is “fond of hyperboles but he really doesn’t intend to do those (warnings).”

Presidential spokesperson Ernesto Abella defended Duterte, citing Article VII, Section 18 of the Constitution that allows the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) Secretary Mike Sueno said he’s in favor of the idea, but applied only in certain areas.

While Duterte has made a habit of speaking off-the-cuff, the media is right to quickly respond to his words, as these carry threats and suggest policy implications. Suspension of the writ of habeas corpus is a repressive instrument and its consideration, however slight, should not be taken lightly.

Leave a Reply