Muddling through aid distribution mess

THE EXTENDED community quarantine (ECQ) has pushed more Filipinos deeper into poverty. The government’s aid has been slow to trickle down and at the rate that things are going, it may not reach those who need it the most in time.

On April 2, the government rolled out its emergency assistance program with a package of subsidies for the poor. Media reported that the “Bayanihan to heal as one Act” or Republic Act 1149 provides for the reallocation of budget items to support the Special Amelioration Program (SAP) from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and wage subsidies from the Department of Labor (DOLE).

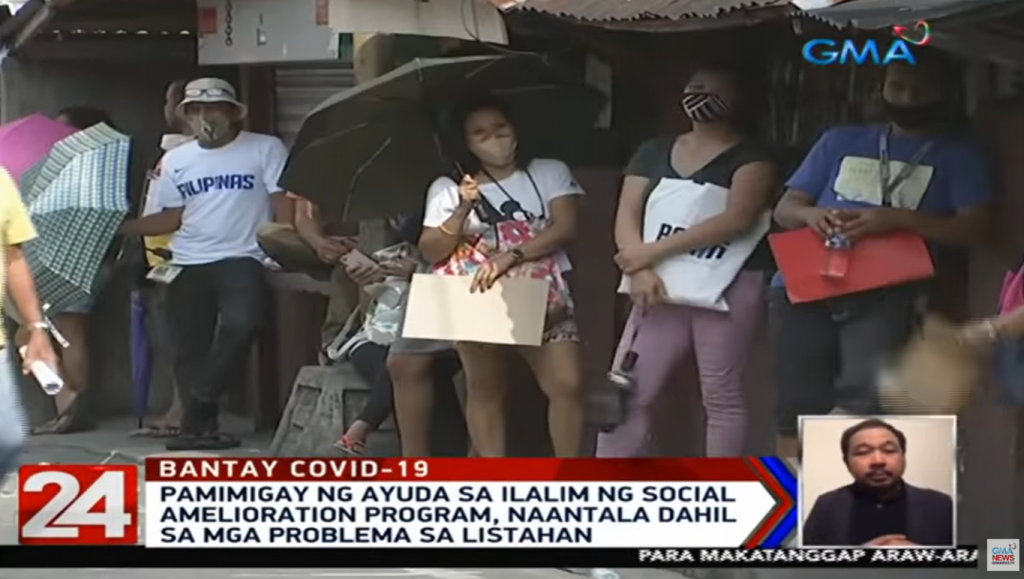

DSWD’s SAP is intended for 18 million low-income families who are entitled to get subsidies of from PHP5,000 to PHP8,000 for two months. But as of April 16, only 4 million families had received their subsidies. Media also reported that many have not received anything.

Unfortunately, the government has thrown its well-intentioned assistance into a bureaucratic muddle, as it failed to work out the important details in its implementation: Who are included in the distribution? What are the criteria for eligibility? What agencies are assigned to distribute? Instructions for distribution were not specific. The president himself did not give clear instructions, except to say that almost everybody was covered.

As the rollout commenced, it became apparent that the implementation had not been thought out well enough. Media were quick to report the confusion between DSWD and local government officials, picking up the criticism voiced by members of Congress. A deep dive into the mess would surely help identify solutions.

Some reports showed how some local governments went on their own to provide for what was lacking, so that those who needed the subsidy could receive something.

CMFR monitored reports from the three major Manila broadsheets (Manila Bulletin, Philippine Daily Inquirer and The Philippine Star); four primetime newscasts (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, CNN Philippines’ News Night, GMA-7’s 24 Oras and TV5’s One News Now); as well as selected news websites from April 2 to April 20, 2020.

Poorly planned

The DSWD and Local Government Units (LGUs) could not agree on who belonged to the category, “low-income families.” The conflicting statements by officials caused chaos and confusion for presumed beneficiaries who had lined up for hours only to be told they were not eligible.

Who exactly are low-income families? An Inquirer report on April 7 had local officials asking the same question. Media followed the exchange as DSWD blamed local governments for failing to present complete lists of target beneficiaries. Meanwhile, local executives said the number of beneficiaries approved by DSWD was lower than the actual count in their communities. They also urged DSWD to be clear with guidelines on beneficiaries, pointing out that the public believed aid would cover all low-income households.

Media picked up citizen complaints. Videos captured the long lines in the sun, the frustration of some and the satisfaction of others. 24 Oras aired a report on April 20, noting discrepancies in the list of beneficiaries, some of which had double entries and still included the deceased.

The problems have surfaced a fundamental weakness in the government system, the failure to keep updated demographic data bases.

Big failure

In his April 20 column, lawyer Joel Butuyan provided a rundown of failures, scoring the government for bungling the cash assistance program on “multiple levels” and bringing “chaos and hostility to every barangay all over the country.” Butuyan noted DSWD’s “muddled” implementing rules, disqualifying many needy families.

DSWD’s rules are so bureaucratic, he wrote, “they fail to consider the “war-like emergency.” He argued that the country needs a “food survival program” and that the country is in a “public health crisis every living generation has never experienced before.”

An April 6 Philstar.com report critiqued DSWD’s handling of the social amelioration program, referring to similar government failures in the past when distribution of disaster aid is fragmented across agencies. Despite the long experience which should have taught officials how to work together during times of disaster, the obvious lack of coordination among agencies bogs down government attempts provide public aid.

Post lockdown scenario

As the ECQ has been extended in the National Capital Region, Calabarzon, Central Luzon, and other provinces until May 15, the government said beneficiaries living in non-ECQ areas will receive aid. Social Welfare Secretary Rolando Bautista assured on April 27 that the families living in non-ECQ areas who have not yet received their subsidies will still get assistance.

The challenge to media is obvious. Journalists should continue to look into the failure of distribution, doing the math, keeping track of what it takes to provide the appropriate subsidies for at least 18 million families and making sure the reallocated funds are not going elsewhere. One of the important functions assigned to the press is to help citizens hold government accountable.

Rappler has started such efforts, with its tracking of DSWD assistance. Hopefully others will do the same and report when finally the said amount has been well spent.

Leave a Reply