Mass testing as policy: Still no plan in sight

AS THE government eases restrictions to start up the economy, cash-strapped Filipinos are eager to return to work. On May 16, modified quarantine conditions were set for some areas, and some 14 million people across the country braved the risk of COVID-19 by leaving their homes to earn a living.

The mandatory testing of workers returning to their jobs could reduce the risks, but both the health and labor departments dismissed the need for it. Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire issued the statement to that effect on May 18, following Paranaque City’s directive requiring testing for workers. On the same day, Labor Secretary Silvestro Bello III clarified that only those showing symptoms of contagion would undergo testing – and at the expense of their employers.

Pressed for his comment in a briefing on the same day, Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said that the government cannot conduct “mass testing” and would leave such efforts in the hands of the private sector.

Much of the media reported the lifting of some quarantine measures, but without any reference to the risks involved as people move more freely. Journalists reported separately that some lawmakers have questioned the capacity of the government to do enough testing necessary to assess the danger of contamination for those returning to work.These reports were looking at the same problem but presented these as though the developments were not connected.

Media’s disjointed news treatment has failed to provide the public a sense of the meaning of these developments. Those who read only about the DOH announcements may think the perils of the pandemic have diminished.

It should be evident that media reports on the different quarantine regimes should still refer to the persistent threat of contagion, a quarantine being intended only to slow the rate of transmission.

Stories about the modified enhanced community quarantine (MECQ) and general community quarantine (GCQ) should thus refer to the issues raised in some quarters: the need for widespread rapid tests and developing systems for contact tracing. Media should also note the need for a massive information drive to remind citizens that the virus has not been eradicated and that they must observe public health measures, such as the use of face masks and social distancing.

Ideally, government efforts should include all the above. But despite the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID), government messages have lacked coherence.

Under these conditions, the media should try to do more than just record official statements. The real story is the lack of a plan, the lack of coordination which doom efforts to control the pandemic. Reporting should alert the public to the government’s failure to resolve internal policy questions. Indeed, it should try and collect the facts so reports can check, and expose as necessary, the administration’s failure to adequately protect the people during the pandemic.

Even though they cited sources that called for mass testing, the media and sources skirted the crucial question –Is the current level of testing providing the government with enough information to make sure that the less restrictive quarantine measures do not trigger a second wave of cases?

CMFR monitored reports from the three major Manila broadsheets (Manila Bulletin, Philippine Daily Inquirer and The Philippine Star); four primetime newscasts (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, CNN Philippines’ News Night, GMA-7’s 24 Oras and TV5’s One Balita); as well as selected news websites from May 11 to May 20, 2020.

Expanded targeted vs mass testing

Confusion continues to hound the government’s discourse on testing.

On May 18, Roque had this to say about the government’s plan for the mass testing of workers: “…pero in terms sa mass testing na ginagawa ng Wuhan na all 11 million (residents), wala pa pong ganyang programa at iniiwan natin ‘yan sa pribadong sektor.”

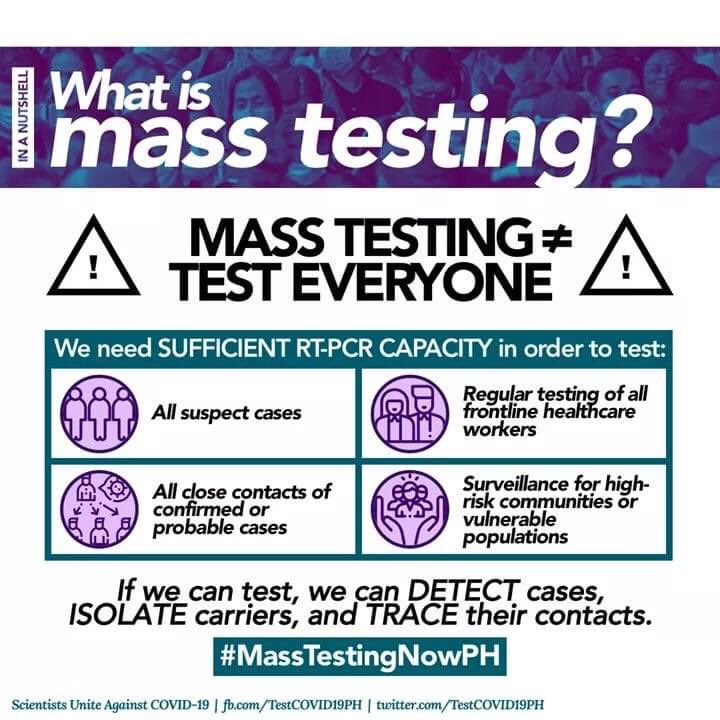

The following day, he cried foul and singled out an online report for allegedly misquoting him, when all it did was quote him. Roque argued that the term “mass testing” is misleading because no country can conduct coronavirus tests on all their citizens. He further explained that the government is carrying out an “expanded targeted testing,” not “mass testing.”

Following this brouhaha, a report by Interaksyon explained the nuances of the terms expanded targeted and mass testing. The report pointed out Roque’s incorrect assumption that mass testing means mandatory testing for the entire population of the country. Groups pushing for mass testing criticized Roque for causing the confusion.

Passing the buck

Officials of the administration have also fudged the issue of responsibility, a matter that unfolded in separate news reports.

In the same briefing cited above, the presidential spokesperson said the government had no plan to implement the kind of mass testing that was done in Wuhan. But he did not say then whether the administration was working to expand targeted testing, or whether the administration was leaving this to the local government to implement.

On May 18, the labor department issued an advisory that officially places the financial burden of COVID-19 preventive and control measures on the private sector.

Meanwhile, on May 20, The Manila Times reported that business groups including the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry (PCCI) and the Management Association of the Philippines (MAP) are still seeking government support for mass testing.

For their part, labor groups are concerned over the welfare of workers. In an news.ABS-CBN.com report, Thadeus Ifurung, Defend Jobs Philippines spokesperson urged the health department and the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) to have “stricter rules and guidelines to private employers to require workers to undergo coronavirus testing.”

Discordant voices in the Congress

Congress echoed the same misgivings. Some reports reported the concerns expressed by several lawmakers about the government’s reluctance to spend for the mass testing of employees.

The Inquirer reported how Sen. Risa Hontiveros joined the call for mandatory mass testing. The Bulletin also reported the views of other senators. Sen. Joel Villanueva, who chairs the Senate labor committee, said that the government should not pass on its responsibility to the private sector. Senate President Pro Tempore Ralph G. Recto recalled the government’s mandate to improve the country’s testing capacity as dictated by the Bayanihan Act.

Rep. Joey Salceda (2nd district, Albay), who pushed for the metro lockdown, highlighted the need for testing and tracing. In a study cited by Boo Chanco in his column for The Star, Salceda said, “ECQ was necessary, but not sufficient. ECQ was a policy designed to help us meet minimum health standards and set up a system of testing and tracing.”

Experts have agreed that quarantine protocols are eased, testing and tracing become more critical. Without these measures in place, the government’s draconian lockdowns may be wasted. Experts have repeatedly said that the numbers presented by officials do not reflect the gravity of the situation because only selected people are tested. A review of media coverage shows that the executive department is alone in ignoring this important point.

Leave a Reply