Have we “flattened the curve?”

Reporting DOH numbers

IN APRIL, as the clamor for COVID-19 mass testing intensified, the government scrambled to scale up its testing capacity. On the 30th, during the regular press briefing of the DOH, Undersecretary and spokesperson Maria Rosario Vergeire admitted that the DOH had failed to meet its target of conducting 8,000 tests daily. But a mere five days later, on May 5, the health department claimed that the country had already “started to flatten the curve.”

Few reports captured the discrepancy between these statements; most reports repeated the figures without explaining what the numbers indicated or whether these justified the health department’s claims that there were now fewer cases, which meant it was “flattening the curve.”

As news accounts merely tracked whatever DOH had to say, only the Op-Ed pages gave the public more meaningful discussions on the role of mass testing in mapping the disease.

CMFR monitored reports from the three major Manila broadsheets (Manila Bulletin, Philippine Daily Inquirer and The Philippine Star); four primetime newscasts (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, CNN Philippines’ News Night, GMA-7’s 24 Oras and TV5’s Aksyon); as well as selected news websites from April 30 to May 10, 2020.

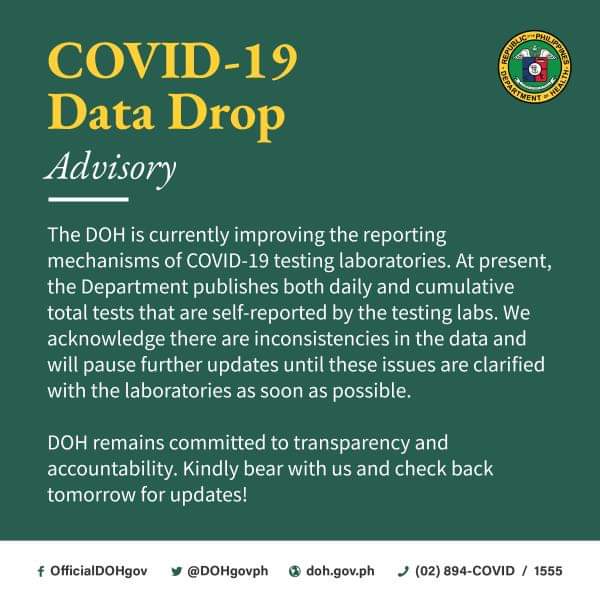

False claims and inconsistencies

As the enhanced community quarantine (EVQ) kept people at home for about a month and a half, the health department in a media forum on May 5 reported that the country is starting to flatten the curve. This was followed by another announcement on May 11 claiming that the number of positive cases had dropped by more than half since the beginning of the outbreak.

Typically, much of the media failed to question these claims. But some news organizations—Inquirer.net, news.ABS-CBN.com, GMA News Online, and CNN Philippines—discussed a policy note released on May 8 by the University of the Philippines (UP) COVID-19 response team that flagged several “alarming errors” and “inconsistencies” on COVID-19 data, including a “continuing mismatch” between the Department of Health (DOH) and local governments’ numbers of patients.

During the Cure COVID press briefing on the same date covered by news.ABS-CBN.com and Rappler, a professor from Ateneo de Manila University also cautioned the public against the government’s claim of “flattening the curve.” Dr. Felix Muga of Ateneo’s Department of Mathematics showed that the epidemic curve or the number of daily new cases reported by the DOH is still moving upward.

Random testing

Columns and editorials provided more analysis to help the public evaluate what was being gained by the quarantine. These took up various points which together questioned how the government was doing the testing, indicating the need to do more than the DOH tests.

Mahar Magahas’ column in the Inquirer said the country’s poor testing capacity could be the reason why we officially have much fewer cases per million persons (1Mpop) than Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia, and Japan. According to Mangahas, the direct scientific way to see the infection rate, and its movement over time, is to survey a random sample of the population, carefully observe the infection rate of the sample by testing, and then repeat the survey periodically. Mangahas argued that the infection rate cannot be statistically inferred from the clinical tests that are currently being conducted in the country.

Economist Solita Collas-Monsod shared the same view. In her May 11 column for the Inquirer, Monsod reiterated the need for data at the local level. She said that using sample-based random testing to find out what is happening to the population—either community-based (LGUs) or sector-based (company or industry), will help determine where, when, or how serious the next wave of the pandemic will be.

Journalists will have to learn to incorporate these points in their reports. Obviously, most health reporters do not have sufficient background in the science of the pandemic and are thus reduced to simply quoting what DOH officials have to say.

The he-said, she-said approach can also result in confusion, as experts may not all agree. The journalist has to work through the maze of different views to provide analytical context that makes sense.

Echoing the government narrative

Unfortunately, media reporting has echoed the government narrative by simply reporting the numbers without probing the inconsistencies that expert groups have raised. Having ignored the need for rapid testing on a massive scale, DOH has stuck with the diagnostic tests which do not provide the real numbers in the spread of the disease. Asymptomatic carriers escape the reach of DOH testing which is why the department’s numbers are not reliable indicators of how well the disease is being controlled.

Meanwhile, some local governments have been actively pursuing rapid mass testing for the purpose of disease control. Close media monitoring of their progress may give the public a better sense of the gains of ECQ and social distancing measures. Reports on the impact of these efforts would be of greater value than the numbers game the DOH insists on playing. Reporting on lessons learned could be more enlightening, not just for the benefit of the public but also the government agencies charged with leading the country through the crisis.

Leave a Reply