Media Review

March 1 to 15, 2020

Every two weeks, CMFR will provide a quick recap of the media coverage of the biggest stories or issues, noting the same slips that our monitors have been doing. We intend this as a quick mapping of news, providing a guide for journalists and identifying gaps in reporting, the lack of interpretation and analysis as necessary. This section also hopes to engage more public attention and participation in current events, and for them to learn the practice of media monitoring. It is after all the public that serves as the best watchdog of press power.

MEDIA DID note the anniversary of the first day of the lockdown in March last year. But reporters did not choose to spend time reviewing all the policy failures that doomed the government’s attempts to address COVID-19. The anniversary should have occasioned a review of how government dilly-dallied about banning international flights particularly from Wuhan, the epicenter of the disease. It could have noted how both the president and the DOH chief seemed to think that the lockdown was all they had to do.

In May 2020, after two months of the strict enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), government had not quite set up a system for widespread testing. Up to the end of the year, only a few LGUs working on their own had implemented efficient contact tracing. The country has remained among the world’s worst afflicted by the disease. The administration, thinking that the lockdown could outlast the disease, ended up wasting whatever gains were made by the quarantine.

The media have not clearly identified these policy failures and the poor implementation of government’s announced actions. The missing critique has whitewashed the shameful performance of government and only the poor ranking of the country’s anti-pandemic performance stands as proof of the Duterte administration’s great disservice to the nation.

We are looking back at a two-week period torn by the push and pull of two issues: the need to lock down because of a surge in cases and the pressure to open up the economy.

Alas, the cheer and relief over the vaccine rollout were all short-lived, as the surge of cases reached hundreds in some cities in Metro Manila. No city-wide or region-wide community quarantine has been implemented yet, but some barangays have imposed localized lockdowns. The Metro Manila Council has imposed a uniform curfew of 10 pm to 5 am as cases in the capital average 2,000 daily. Meanwhile, national agencies are still in a bustle of efforts to get people to go out and spend money because the economy needs boosting.

Vaccine rollout

The country’s vaccination drive for COVID-19 officially started on March 1 with only 600,000 donated doses of China’s Sinovac available for the launch. Less than 500,000 doses of AstraZeneca arrived later on March 4.

Media dutifully followed the ceremonials in the first hospitals to get the vaccine, noting which medical workers were first to get inoculated. Reports noted the low turnout on the first day of vaccinations, citing in-house hospital surveys that showed a drop in the number of willing participants when they were informed that only Sinovac was available on the day of the rollout.

Reports, however, did not probe further to explain the root of this apparent hesitancy. Instead, journalists relied on quotes from medical workers who said they chose to be protected early because of the risk of exposure along with government officials who chorused: the best vaccine is the one available; other accounts followed representatives of health worker unions who maintained that the sector deserved the best protection.

Media coverage glaringly lacked the controversial background of the primacy of Sinovac in the rollout. No reference was made about the assurance that Pfizer and AstraZeneca would arrive much earlier in mid-February; or the IATF’s overturning of the FDA’s earlier decision not to recommend Sinovac for the health sector because of the low rate of efficacy demonstrated in the experience of Brazil. Media effectively echoed the government line that the best vaccine is the one on hand.

CMFR mapped the developments prior to the vaccine rollout, noting the government lapses that led to the Philippines being the last to vaccinate among ASEAN members. (See: “PH government’s slow vaccine rollout: Plainly inept or intentional?”)

Surge in COVID cases

With the rise in new cases averaging in the thousands, the government has not announced any plan to address it, leaving it to the LGUs to set the localized quarantines themselves. So far the vaccination plan seems to be going slower than expected, something media should examine apart from noting Duque’s assurance that the pace of vaccinations will soon pick up. Government officials were typically quick to blame people who were not observing prescribed health protocols, which then justified increasing police manpower on the streets to go after non-compliant citizens.

It seems as though we have simply turned back to the same chapters of affliction we already suffered last year, including the lack of competent leadership.

Media did not have much to say about the new variants and the understandable fear these raised in the national capital. Similarly, journalists failed to emphasize the observation that restrictive and punitive measures, which had been implemented at this same time last year, will have limited effects if not combined with health-based strategies.

Reporters did not raise the contradiction between the facts on ground and the administration’s insistence to open up the economy without joining this to a high level of preventive measures, the speed of vaccination, the availability of vaccines, and a vigorous communication campaign to remind people to keep observing minimum health protocols.

Still less examined was the expectation that businesses based on travel and entertainment would automatically revive as soon as they are directed to open.

Police atrocities

As though the pandemic were not enough of a plague, an epidemic of killings seemed to have broken out in the open, once again with the police at the center of it. Of course, the president was again heard to order “kill” in pushing for his drive to end the insurgency.

Nine activists were killed and six others were arrested in the Calabarzon region on March 7. Per news reports, police maintained that they were serving search warrants in accordance with standard protocol. Eyewitnesses and families of the victims disagreed and said the operations were outright executions.

Media dubbed the crackdown “Bloody Sunday,” following developments such as the refusal of the police and military to discharge the bodies from the funeral home, and to let the families take the remains. Media also reported that the lawyers of the families and journalists trying to cover the discharge were being blocked by the police. News quoted Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra saying he was “disappointed” that killings continued despite his recent statement before the UN pointing to irregularities in drug war operations.

CMFR cheered Rappler’s scrutiny of drug war documents, which revealed evidence of police culpability and affirmed Guevarra’s admission of the same before the UN Human Rights Council. The analysis should be a constant reminder of the dangers of police ignoring their own protocols and the impunity with which they violate due process and human rights. (See: “Rappler reviews evidence of police culpability in drug war killings”)

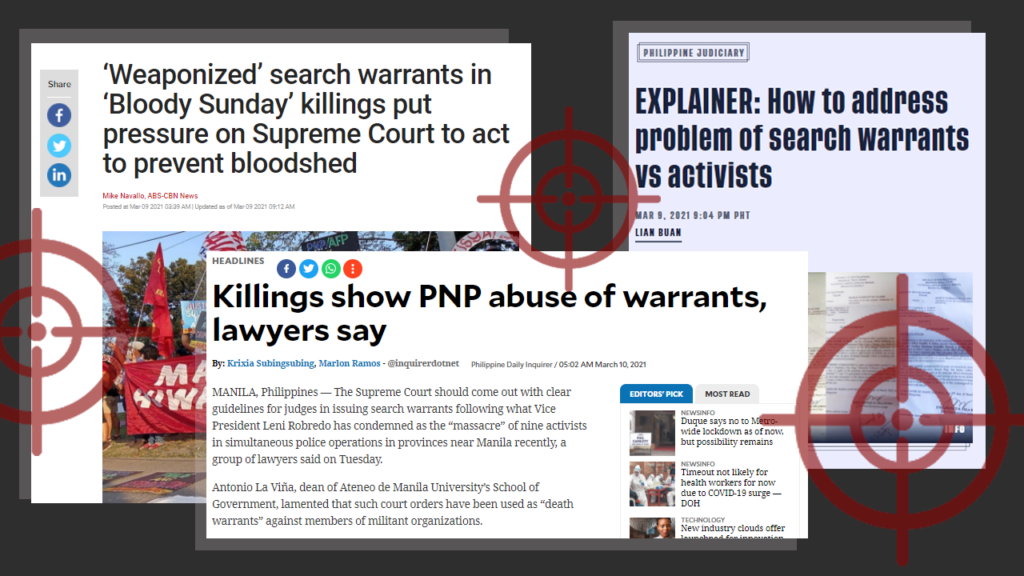

Notably, Inquirer, Rappler and news.ABS-CBN.com went further to call attention to the phenomenon of search warrants being weaponized by law enforcement, and that the Supreme Court should take steps to address the issue.

Journalists also reported that P. Lt. Fernando Calabria, Jr., the intelligence chief of Calbayog City Police, filed a request before the Office of the Clerk of Court asking for names of legal counsels of alleged communist-terrorist personalities. Media reported condemnations from the Integrated Bar of the Philippines and the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers, both of which emphasized that lawyers should be able to exercise their profession without fear and discrimination. Claiming he was acting on orders of higher officials, Calabria was sacked on March 13.

Police were also involved in the killing of Calbayog City Mayor Ronaldo Aquino on March 8. Initially calling it an ambush, the police backtracked to say the incident was a shootout between their forces and the mayor’s security team. Media reported on March 14 that Lt. Col. Neil Montaño, the city’s chief of police, was ordered dismissed by the national headquarters for command responsibility.

To add to concerns about human rights, the House of Representatives passed on third and final reading House Bill 7814 that seeks to amend the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002. The bill has been criticized by human rights groups and opposition figures for listing conditions when the police can “presume” a person’s guilt, which reverses the presumption of innocence until proven guilty.

Not too early to campaign

As the virus and violence continue to threaten Filipinos, Duterte and his allies found time to engage shamelessly in premature campaigning. Duterte’s political party, PDP-Laban, floated a resolution urging him to run for vice president in 2022. Duterte, meanwhile, endorsed Senator Christopher “Bong” Go as the next president in a separate public event.

Earlier in February, presidential campaigns for Sara Duterte-Carpio, the presidential daughter, intensified with publicity materials scattered across many provinces. Ms. Duterte and Go both feigned disinterest in the position, but this is all old hat when one recalls Rodrigo Duterte’s “is he or isn’t he?” campaign tactic to make sure he got enough space and time in the news throughout 2015 before the official filing of certificates of candidacy.

Leave a Reply