Lessons learned from EDSA this 2023

This Week in Media (February 20 to 26, 2023)

THE SILENCE from the Palace last week as the 37th anniversary of EDSA People Power approached suggested that the national holiday would be forgotten or ignored on the first year of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as president.

By the evening of February 23, information from Malacañang was limited to the declaration of February 24, not the 24th, as a special nonworking day, presumably to commemorate the EDSA anniversary. The event had been observed by past administrations with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Rodrigo Duterte sent messages but never attended any ceremony. Through the years the celebration has evolved into a program planned by the government, and remote from the people who faced tanks and waved flowers and rosaries at Marcos’ troops—the men and women who called a peaceful end to his brutal regime and protection.

Almost all presidents post-EDSA have declared February 25 as a special nonworking holiday through official Proclamations. Observing “holiday economics,” only former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo moved the commemoration to February 23 in 2009 and February 22 in 2010, making the holiday a working day and “for schools only.” Marcos’ decision to make February 24 a nonworking holiday was sudden enough. Rappler’s Bea Cupin noted last February 23 that the Palace did not answer media queries on President Ferdinand Marcos’ plans for the 25th.

Media covered the nongovernment activities and programs in different parts of Metro Manila organized by civil society groups; some online news reports provided a list. On February 24, different news organizations reported that the president had flown to Ilocos Norte for an Ilocano festival. Lourd de Veyra in his TV5 segment and Cupin in another Rappler story noted that all past presidents commemorated EDSA in different ways, including simply issuing messages as Rodrigo Duterte did.

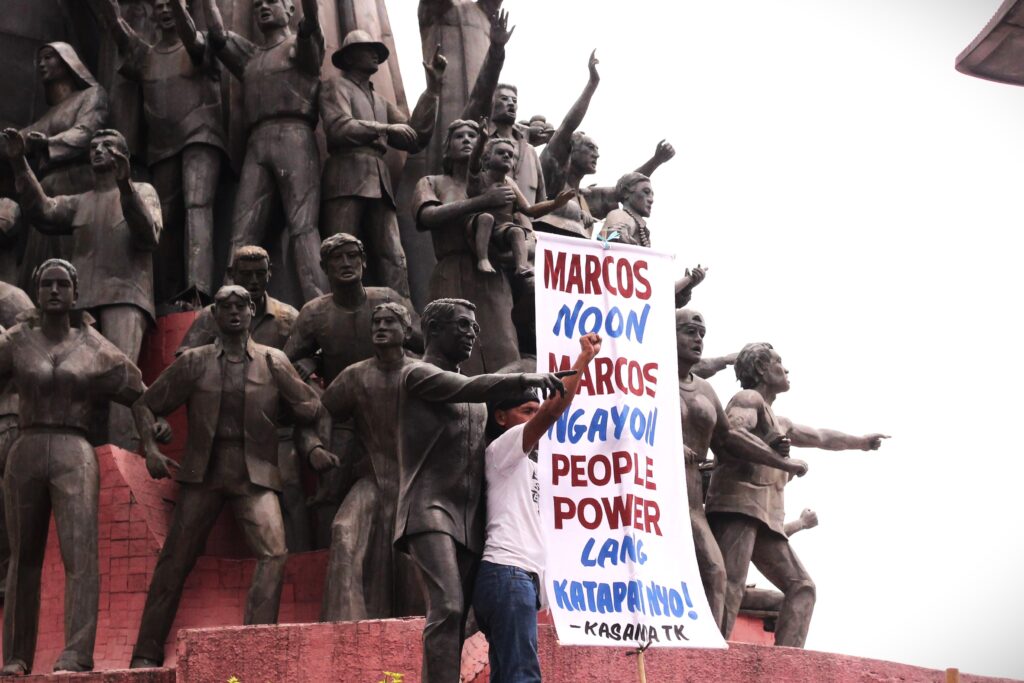

Despite his absence in Manila, media made much of Marcos’ gesture of sending a wreath to the People Power Monument on February 25. News accounts in print, TV and online featured the photo of the wreath bearing Marcos’ name, but without any other message. Most news accounts highlighted the President’s statement issued on February 25 in which he said that he was offering his “hand of reconciliation to those with different political persuasions.” An Inquirer feature on Sunday tried to include the competing ideas at play: “Marcos Sr.’s son, the President, offered a wreath of white flowers with no message attached” – a grand but empty gesture.

News accounts readily quoted parts of the full statement in their February 26 editions, including Marcos’ remark that he shares in the public commemoration of “those times of tribulation and how we came out of them united and stronger as a nation.” The Daily Tribune even posted as banner headline “PBBM humility marks EDSA day.” However, activists cited in The Philippine Star, Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Manila Times and GMA-7’s 24 Oras said there could be no reconciliation until Marcos and his family acknowledged and apologized for the atrocities committed during his father’s regime.

Broadcast media did not provide a live feed to air in their entirety or even in parts the three main gatherings along EDSA on February 25: the wreath-laying ceremony at the People Power Monument led by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) and the Quezon City government; the program organized by the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses and Martial Law (CARMMA) and other activist groups held after the ceremony at the People Power Monument; and the Tindig Pilipinas-led cultural gathering at the EDSA Shrine, which culminated in a concelebrated Catholic Mass.

ABS-CBN and GMA-7 reporters were onsite to report these events. But the reports of TV Patrol and 24 Oras gave little information about the groups involved, and how they worked together to hold the memorial programs, which judging from the social media exchange suggested the participation of EDSA veterans — including those who marched in the parliament of the streets for years before 1986 — and a generation of young Filipinos who clearly wanted to know more about that crucial moment in history.

Other than visual notes and soundbites from key figures, the reports did not ask those in attendance why they chose to participate in EDSA activities this year, whether as first-timers or as veterans.

Lessons from EDSA

Media focus on events and statements of the day sidelined discussions of the real significance of EDSA. An exception, CNN Philippines’ The Final Word drew out key insights from Rico Hizon’s interview with Xiao Chua, an academic and historian. Chua stressed the reality of EDSA as a people’s victory against a dictator, not a feud between two political families.

Hizon noted how government does not seem to regard EDSA as significant, that Marcos even changed the date of the holiday and more activities were organized by civil society. Chua said only the NHCP is mandated by law to observe People Power with the dignity of rite and ritual, adding that retaining the 25th as a holiday stresses the significance of what happened as history. But despite the attempts to diminish its significance, those who want to celebrate EDSA will always do so for as long as they can.

Asked whether the election of another Marcos meant the democracy and freedoms regained after EDSA have been forgotten, Chua told Hizon that the victory of Marcos is just one aspect of it. He said the past administration of Duterte played a key role in the return of a Marcos to the presidency, and that public frustration over the failures of all post-EDSA administrations has led to disillusionment with democracy. Chua noted that most anti-democratic efforts utilize political power and money, but thankfully, there remains some pushback from the people.

Manila Bulletin‘s editorial echoed the same idea, pointing out that following an era that curtailed fundamental freedoms, “Constitutional democracy is EDSA People Power’s enduring legacy.”

Several media reports also carried the Social Weather Stations Survey results publicized on February 23 that 62 percent of Filipinos believe the EDSA spirit is still alive, and that 57 percent said it should be continuously commemorated. However, 47 percent also believed only “a few” promises of EDSA had been fulfilled.

Comments agreed on the validity of this sentiment. May Rodriguez, executive director of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation, told 24 Oras that good governance and lasting peace require continuing efforts. The Inquirer‘s editorial echoed the same view: “As we learned every year after 1986, the promise of the peaceful revolution is a work in progress. In those three decades, upheavals and challenges showed us that preserving democracy and hard-earned freedom is never finished.”

Philippine media in the form of the alternative press played a key role in galvanizing the common will among different people to stand together against the Marcos, Sr. regime. Their work included the mimeograph or xerox press, and the underground publications of insurgent groups. After opposition leader and Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was killed in 1983, a clutch of news magazines provided news that could not be found in the Marcos crony press, and provided the information that at other times in our national history the people needed.

The lessons of EDSA have yet to be fully understood or documented at this point. Media play a role each year to plumb deeper into the experience of the four days of February 1986, as well as the long struggle that made EDSA possible. Reporters should find the rich sources of these stories, the gatherings of older people, memoirs, studies of the People Power phenomena and the nameless numbers who made it happen.

The danger of short memory hobbles the experiment of understanding. Past history can be easily forgotten, its lessons dismissed as irrelevant. And history does repeat itself but never exactly. Journalists whose trade stresses the current and the present could actually do a better job knowing and understanding the past. Even with the radical changes in the landscape of news and media, some fundamentals remain. The obligation stands: to honor hard-won victories so the press in the country can be truly free and Filipinos can be sovereign citizens and not servants of the state.

Leave a Reply