Protests in the Philippines: Nepal and Indonesia’s Uprisings Linked to a Philippine Legacy

RECENT PROTESTS in Nepal and Indonesia have sparked a pressing question for the Philippines: Are the corruption scandals over the flood control projects taking the country to the brink of a mass uprising?

In Nepal, protests erupted on the streets of Nepal on July 21, 2025, and lasted for weeks. Led by Gen Z youth who were angered by corruption, inflation, and the social media ban, the movement quickly swelled into tens of thousands occupying streets in Kathmandu and other major cities. By early August 2025, relentless rallies and clashes with police had forced Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal to resign, stunning the political establishment.

Meanwhile, in Indonesia, large-scale demonstrations broke out on August 5, 2025 against a controversial constitutional amendment and widespread graft scandals. Student groups, trade unions, and civil society coalitions spearheaded the movement. Over the next two weeks, protesters clashed with security forces in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and Surabaya. Facing growing unrest amid state killings, several cabinet ministers had resigned and on August 20, forced President Joko Widodo to suspend his planned constitutional change.

The upheavals in the region showed how public rage—especially among the young—can rapidly evolve into regime-shaking revolts. The investigation of corruption scandals in the Philippines has caused similar unrest. Nationwide protests on September 21, 2025, timed with the commemoration of the Proclamation of Martial Law (September 21, 1972), revived comparisons to the country’s long history of street uprisings.

A Legacy of Protests

For over half a century, Filipinos have repeatedly turned to the streets to confront corruption, authoritarianism, and political abuse. From the militant student uprisings of the First Quarter Storm, the EDSA People Power Revolution that stirred the world in 90s, and EDSA Dos which ousted a sitting president, mass protests have caused critical turning points in recent Philippine political history. In the decades that followed, rallies and strikes have expressed public anger over electoral fraud, press freedom, labor rights, and government corruption to prove the power of street mobilization to hold government accountable.

This tradition – a historical background that continues to hover with every political crisis caused by abuse of government power by elected leaders – forms the backdrop to today’s political climate. Understanding the history of these uprisings helps explain why the Philippines is once again on the cusp of mass mobilization and why we were never far from Nepal or Indonesia.

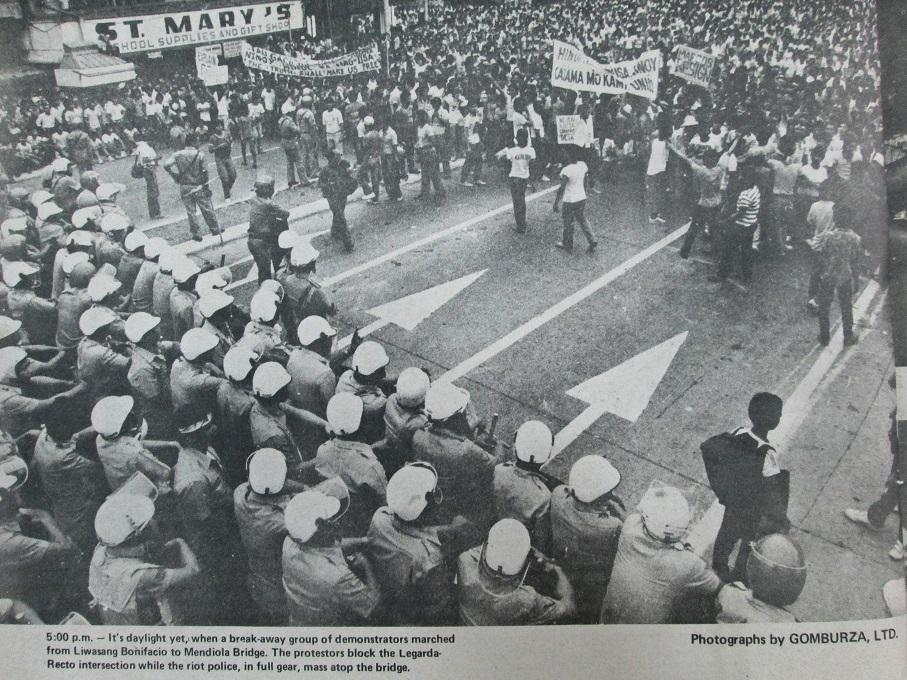

1. First Quarter Storm

The First Quarter Storm marked one of the earliest mass uprisings to roil the long-standing regime of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. From January to March 1970, tens of thousands of students, youth groups, and activists staged large demonstrations against the administration’s corruption, cronyism, and rising authoritarianism. Sparked by protests during Marcos’ State of the Nation Address on January 26, 1970, the movement quickly escalated into a wave of unrest involving violent clashes with police and military. The sight of student demonstrators battling riot police on the streets of Manila marked a turning point in Philippine political activism. Dispersed through violent police action, the FQS left a deep imprint on Philippine political history and served to radicalize a generation of youth.

When Marcos declared Martial Law on September 21, 1972, activists who emerged from the FQS would go on to become central figures in later democratic movements, planting the seeds of a protest tradition rooted in defiance of dictatorship as well as corruption in public office.

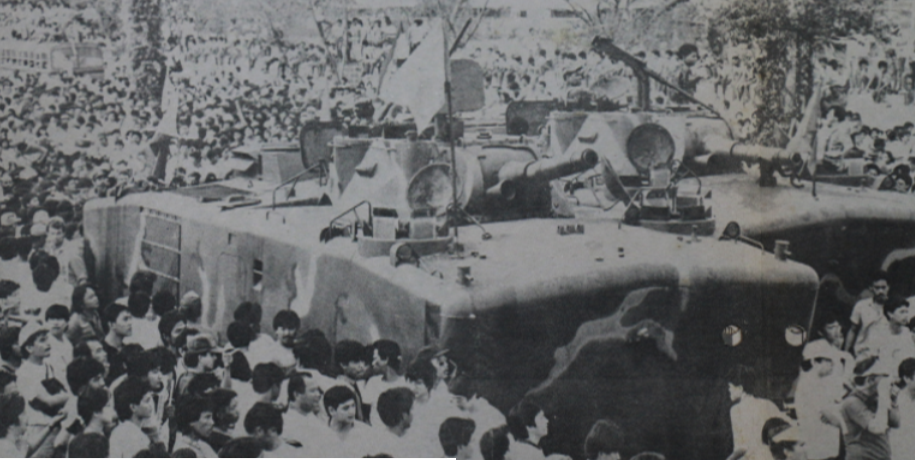

2. 1986 People Power Revolution

EDSA was the culmination of years of civil resistance to two decades of dictatorship under Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, the former as president and the latter as First Lady and later governor of Metro Manila. Triggered by massive election fraud during the snap elections on February 7, 1986, followed by military defections, Filipinos gathered in EDSA to demand his ouster. For four days in February, a human tide of civilians, nuns, priests, professionals, and students formed barricades, faced down tanks, providing food and support to mutinous soldiers, and resolved against the use of violence. Protests in other cities expressed dissent and discontent nationwide.

The peaceful uprising became a global symbol of nonviolent resistance which effectively restored democratic institutions under the leadership of Corazon Aquino. EDSA 1’s success showed how civilian unity and military defections could topple an entrenched autocratic regime without bloodshed. The iconic event not only reshaped Philippine politics but also inspired pro-democracy movements around the world.

3. EDSA Dos

Fifteen years later, the Philippines saw a second EDSA uprising. Dubbed EDSA Dos, the protests erupted in January 2001 after the impeachment trial of then-President Joseph Estrada collapsed on January 16, 2001 when the Senate refused to open an envelope that held a crucial piece of evidence that would prove the involvement of their members in corruption. The event sparked public outrage; as citizens flocked to EDSA, joined by students, civil society groups, religious leaders, and eventually segments of the police and military.

The protest drew hundreds of thousands over four days, forcing Estrada to resign, departing from Malacanang. With less speed and spontaneity than EDSA 1, EDSA Dos still demonstrated how People Power could mobilize public protest and force a sitting president to give up power, causing regime change without an election.

4. Other Major Protest Waves (2000s–2020)

Through the first two decades of the millennium, corruption scandals and abuses of presidential power would drive Filipinos to the streets to denounce and protest abuse of power in high office. Even without the high drama of the EDSA People Power Revolution or EDSA II, these episodes served as effective reminders of the capacity of public protest to hold public officials accountable.

• Hello Garci (2005)

Doubt and widespread speculation surrounded the election results in 2004. Sparked by the release of wiretapped recordings allegedly capturing Gloria Macapagal Arroyo conspiring to rig the 2004 elections, tens of thousands marched in Makati and other urban centers. Protesters from the opposition, leftist groups, and civil society demanded Arroyo’s resignation, decrying electoral fraud and the erosion of democratic processes. While Arroyo held on to her position, the uproar damaged her authority, weakened her public standing, and deepened political polarization.

• Million People March (2013)

Outrage over the Priority Development Assistance Fund scam (PDAF scam) ignited the Million People March in 2013. Allegations recounted how lawmakers funneled billions of pesos in pork barrel funds to fake NGOs enabling them to use these funds themselves. The anger expressed on social media snowballed, calling citizens to gather at Luneta Park on August 26, 2013. Tens of thousands from varied sectors responded, demonstrating the power of social media and digital platforms to mobilize public protests.

• Anti-Terror Law protests (2020)

After Rodrigo Duterte signed the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 on July 3, 2020, youth groups, human rights advocates, lawyers, and academics staged nationwide rallies warning that the law would be weaponized to silence dissent. Despite pandemic restrictions, protest actions took place in universities, streets, and online campaigns, underscoring fears of shrinking democratic space.

Sectoral and issue-based protests have remained a constant feature of Philippine dissent. Jeepney transport strikes—led by groups such as PISTON and Manibela—have paralyzed major urban routes to protest fuel price hikes, fare policies, and more shortly, the government’s Public Utility Vehicle (PUV) modernization program. Labor Day calls out organized workers, while teachers’ unions and youth alliances mount nationwide protests over low pay, education budget cuts, and campus repression. Environmental organizations and peasant movements have gathered their forces against destructive mining projects, land grabbing, and agricultural neglect.

Though often smaller and issue-specific, these protests show that political action and street protests are rooted in the continuing neglect of the majority of the population, involving livelihood, food, shelter, and other basic issues of social justice.

Even without a singular flashpoint, smaller but persistent protest actions continue to mark milestone dates on the political calendar, including the assassination of leading opposition leader against Ferdinand Marcos Sr., Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. (August 21), and the declaration of Martial Law by Ferdinand Marcos Sr. on September 21. Student groups, progressive organizations, and survivors of martial law use these dates to spotlight corruption, human rights abuses, and historical revisionism. These actions keep the country’s protest tradition alive—and remind the public of its power to resist authoritarian drift.

Echoes of People Power

Media outlets ABS-CBN, Rappler, and Sunstar Cebu linked the protests in Nepal and Indonesia to the Philippines’ “People Power.” Coverage of the protests last September 21 highlighted fears—or hopes—that a “new EDSA” could once again emerge as a reminder of the continuing public need for social justice in the country. This frame effectively highlights the social reform that has yet to ensure equal rights and opportunities for all Filipinos, and that elected officials commit to this goal in national politics and governance.

The tradition of public protest can inspire and promote political values at every level of politics, as exercised by voters and those they assign to power and authority. Every major protest must hold up this goal, to recall and enliven the memory so that generations can draw from this history the collective power that democracy extends to all citizens, the power of choosing leaders and keeping them acountable to the people. The power of EDSA is empty if it cannot call the people and the generations to come, to commit to this national transformation.

Will the Youth Rise Again?

Anger over corruption scandals and elite impunity may continue to fuel calls for nationwide protest rallies. As in Nepal and Indonesia, where Gen Z and students led the charge, Filipino youth are again at the forefront of political action, organizing and consolidating the discussions for future action. This underscores the power of continuity.

In moments of crisis, Filipino citizens—especially the young—must be ready to act, not just through public demonstrations, but through consistent critical feedback when those in authority stray from their responsibilities to the people who gave them the power.

The reminder must be visible at all times, the power given by the people can be taken away – swiftly and suddenly.

Leave a Reply