Government ’s role in the spread of disinformation

First of two parts

EVEN BEFORE the pandemic, countries around the world showed up the symptoms of a social and political disease. Only a few have emerged unscathed from the affliction. Sadly, the Philippines has been noted among the worst cases as disinformation and political lies have taken root, showing up in all aspects of society.

In 2018, Katie Harbath, Facebook Global Politics and Government Outreach Director, famously called the country “patient zero for the war on disinformation.” Sufficient evidence has been gathered by experts and scholars to support Harbath’s description. In the May 2016 Philippine elections, the impact of online political disinformation shaped electoral outcomes at a level that had not been observed before.

Duterte’s campaign laid the ground for his drug-war, as he campaigned about the drug menace as the primary problem of the Philippines, talking as thought the country had become “a narco-state.” In truth, as Pulse Asia surveys showed, the top of the mind issue in 2016 had been improving pay of workers, Duterte did succeed in pushing the drugs and criminality agenda. At the time, the drug problem in the Philippines was not among the worst as measured by international agencies.

CMFR recalls media efforts to check Duterte’s claims which hyped the drug problem. Reuters reported that contrary to his claim of 3.7 million, the Dangerous Drugs Board only listed 1.8 million drug users as of 2015; while VERA Files fact-checked Duterte’s claim that Iloilo was the “most shabulized” province of the country when its ranking was not even in the top fifty provinces.

Weaponizing online propaganda

In October 2016, some months after the elections, Rappler examined the use of social media in the campaign of then presidential candidate Rodrigo Duterte and published its findings in a three-part series by Maria Ressa and Chay Hofileña. “Propaganda war: Weaponizing the internet” identified May 2016 elections as the “first social media elections,” and revealed the “death by a thousand cuts” strategy, entailing the “chipping away at facts, using half-truths that fabricate an alternative reality by merging the power of bots and fake accounts on social media to manipulate real people.”

In 2017, Rappler discussed in an in-depth report how the disinformation network continued its operation from electoral campaign to administration. The report revealed how pro-Duterte bloggers had become “state-sponsored” and “legitimized” after the Duterte administration gave them political appointments, “access to those in power, consultancy contracts, and allowances.”

In January 2017, #LeniLeaks demonstrated the close links between social media influencers and the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO). Press Secretary Martin Andanar called attention to the email threads implicating then Vice President Robredo to a alleged conspiracy to oust Duterte. The sensational claim was picked up by mainstream media. But it was eventually exposed as a false allegation that involved among others two major social media personalities who were later interviewed by Andanar on his podcast. The two along with Mocha Uson, reflected the ties that bound the social influencers to government either with official positions or special access.

“Political clients” and state-sponsorship

Scholars subjected the Philippine case to academic scrutiny.

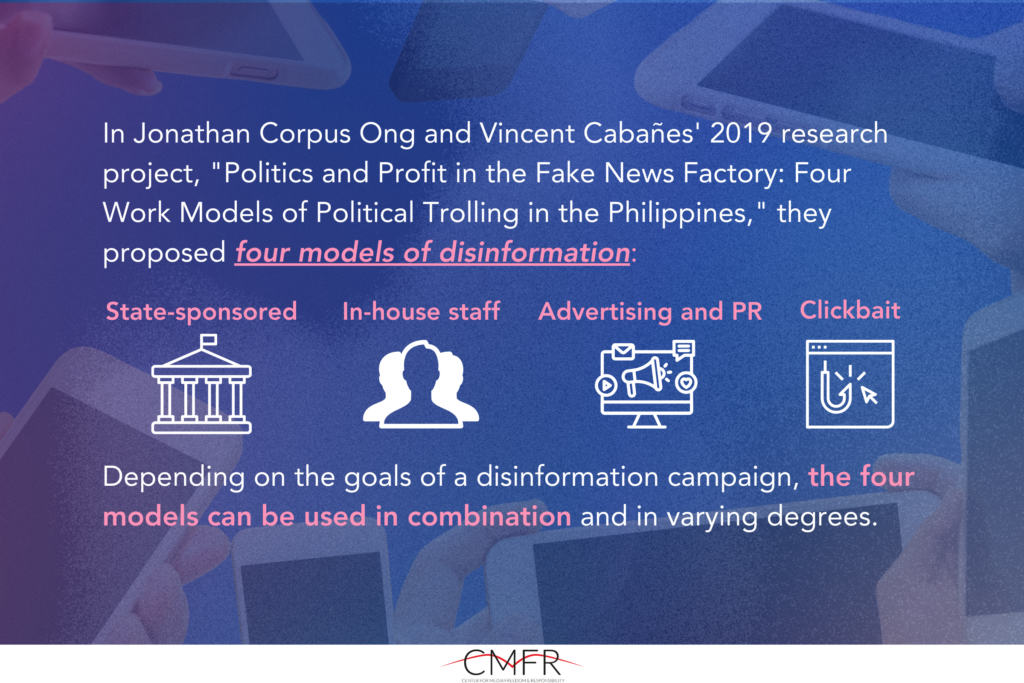

In 2018, Jonathan Corpus Ong and Vincent Cabañes issued a landmark study of the experience of disinformation. “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines,” shed much needed light on disinformation’s effect on the May 2016 ballot. It described how social media amplified the grassroots support for Duterte and recalled how legions of “trolls” and “cyber pests” echoed his use of “gutter language.”

The study revealed the inner workings of political disinformation in the country by identifying the actors, roles, and relationships of these to map out “a blueprint of the architecture of networked disinformation in the Philippines’ digital underground.” The disinformation network studied by Ong and Cabañes had been active in the May 2016 elections and had continued to operate after the polls.

The researchers identified a hierarchy of players in the service of “political clients.” These “political clients” initiated the entire process by approaching the “chief architects” for their services.

According to Ong and Cabañes, the network was structured as follows:

- “Elite advertising and PR strategists” who served as “chief architects,”

- Digital influencers of two kinds: “anonymous influencers” and “key opinion leaders;” and at the bottom level,

- Community-level fake account operators.

Ong and Cabañes’ study made plain the participation of politicians’ in the spread of lies and falsehood, which in Duterte’s case started out by helping to put him in power and continued throughout his term to support his administration. Without the support of politicians, political disinformation networks would have no starting point and no means to operate. The study provided academic evidence to strengthen Rappler’s earlier claims made in 2016 and 2017.

In 2021, Rappler published an investigative report to further confirm the role of government as sponsor in political disinformation. It included discussion of celebrities, social media influencers, and private digital marketing groups that likewise profited from spreading disinformation. These groups were described as amplifiers of “questionable websites and posts containing government propaganda and false information,” to favor the Duterte administration and reinforce its pro-government narratives.

These efforts to study disinformation have now built up the solid foundation and a shared framework of understanding. Presidential candidates who eventually won had used lies and falsehoods, half-truths, hyperbole in presenting their candidacies.

But mainstream media failed to include any of these discussions in the coverage at the time. While Rappler provided sufficient leads, other news organizations chose not to follow up leaving the truth to be consolidated by academics. It did not become the truth that ruled the public mind.

Democracy and Disinformation

In 2018, the media and the academe worked in partnership to hold the 2018 conference titled “Democracy and Disinformation: How Fake News and Other Forms of Disinformation Threaten Our Freedoms, and How to Fight Back.” Led by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the two-day international conference aimed to galvanize “journalists and bloggers, scholars and students and scholars, advertising professionals, and PR practitioners,” to stand against “fake news.”

However, as with the problem of disinformation itself, the pioneering conference received limited coverage from mainstream media. While the event “wasn’t exactly ignored,” the late Prof. Luis V. Teodoro, CMFR Trustee, in 2018 described the lack of coverage as “illustrative of much of the press and media’s incapacity to understand the threat to free expression and press freedom of the current regime of disinformation, and their inability to transcend the political and economic interests that divide them.”

Mainstream media’s coverage of the disinformation problem has since improved. Many newsrooms now issue reports to help public understanding of the problem of disinformation. Various media organizations work together in fact-checking initiatives. But by this time, the political silos had enveloped netizens in echo chambers. The public gulling seemed cast in stone awaiting another reprise in the May 2022 elections.

ALSO SEE: “Part 2: Marcos follows Duterte’s model of disinformation“

Leave a Reply