Marawi, Moving Forward: Notes from the Forum, Media on Marawi Organized by the Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility (CMFR)

VIOLENCE TORE at the heart of Marawi City, the historic capital of Lanao del Sur as fighting broke out on May 23, 2017. It seemed to most residents a most ordinary day, recalling what tasks had occupied them, even the thoughts they were thinking as they waited for someone to arrive or for a meeting to end at the moment they were made aware of the clash between armed men and government troops. Not everyone saw the action, but everyone would be affected; their lives would change, and the place they called home altered forever.

Locals shared photos of men carrying the ISIS-flag roaming the streets, the first recording of the outbreak between the military and the Maute group. No one had any idea about the seriousness of the crisis that would last five long months.

The media reported what they saw, but reporters knew they could see only a small part of the conflict. What they reported was governed by the rules of coverage and they reported what they could, under the watchful eye of the military.

Even if one followed the news about Marawi, Filipinos elsewhere in the country would end up knowing so little about so much. Although media covered the fighting, the casualty list would be incomplete, and months after the end of the war, many are still looking for loved ones. Like many wars, rehabilitation and rebuilding would be another story in itself.

Moving the Discourse Forward

With support from the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Manila, CMFR held a forum on April 26 to present to some 70 representatives of various stakeholder groups its study of the media coverage based its findings based on a content analysis of media reports during the period of five-months (Media on Marawi: Coverage of the Siege).

Among the objectives in holding the forum: to move the discourse forward to examine the future of the broken community, and to engage the afflicted, along with the military and the media, to review their respective shortcomings which prevented perhaps a more coherent and comprehensive response to the challenge of an ISIS-inspired local terror group in Mindanao.

The forum presented three panels featuring the perspectives of the media, the military and civil society.

Media:

Government and Civilian Government:

Local Civil Society Organizations:

The forum established agreement about the need for media to observe operational security and their own safety. Reviewing the experience and the roles their sectors played, there was also consensus about lessons learned and mistakes to be avoided.

Journalists were aware of the limits of what they could report but pointed out that the military controls did not give them too much room to look for stories outside of the military point of view. Reporters also noted how difficult it was to get the people of Marawi to speak out or to talk to the media, observing their fear. They admitted the lack of focus on the Maranaos and the failure to draw out what the community thought about how to end the fighting, and what efforts could have been pursued to bring the Mautes and their followers to lay down their arms.

The military heard the complaints about the overreaching efforts to control the flow of information, which hopefully will lead to rethinking the dynamics of press-military relations. Recognizing the paramount need to protect operational security, other stakeholders spoke about the people’s need to know.

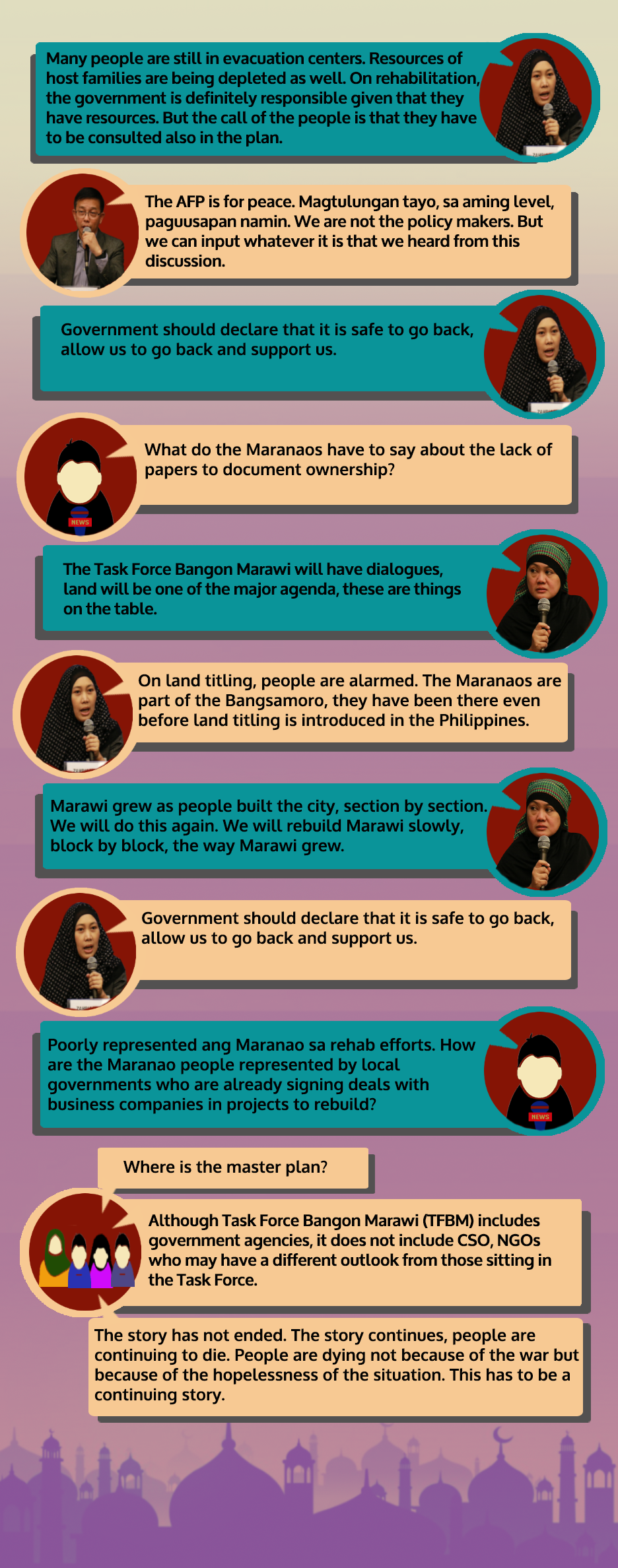

Most importantly, the forum provided a venue for the voices of the community, not just about the loss of their homes and their loved ones, but also on their need to be heard about the plans for rehabilitation and rebuilding of their own city.

CMFR’s Findings

MILITARY DOMINATES COVERAGE

War involves the military in a central role, defending the country’s security against attack and protecting its citizens. It is expected that the military should receive the most attention from the media. But the military’s authority and responsibility operates only in the critical field of battle, which however paramount in importance, is still limited in scope in terms of the reality of war. The dominant information provider withheld much about what they knew and left the media to find for themselves information about ground zero. It could not provide information about evacuees, nor track the flow of Marawi residents to other provinces to join their relatives.

Recommendation:

Clearly, the military plays a key role and is prepared to provide information according to its objectives. Unfortunately for the military, there were conflicting statements in terms of assessing the challenge they faced. This raised questions about what actually they knew about the reality of the crisis. However, given the dominant role that the AFP played, it did maintain its control over the flow of information and regulated the movement of the media, something which media felt should be reviewed so everyone can agree on how much control is necessary in different situations.

Other government agencies should be as prepared to deal with the issue of public information. In a crisis of any kind, be it war, disaster, even accidents. Effective governance involves communication. Each agency needs to assign a spokesperson(s) on the ground, and must be on the scene to handle the information crisis that is part of every crisis. Government communication must define the scope of responsibility and make available updates on a regular basis.

A huge information gap marred the services of various departments who did not set its information policy to be implemented by skilled spokespersons. While the media should persist in getting information even when this is difficult to do, the supply end of information must do its part to provide information that will help the afflicted as well as those outside the crisis who can benefit from the knowledge of those working in the evacuation camps, The same applies to NGOs.

It is perfectly acceptable for media to say that the numbers being given are not yet complete, comprehensive, or just estimates. Nobody expects everybody to know exact numbers at a given time, but there should be a system of keeping track of the numbers, not just of the dead, but of the missing, of those who left their homes as well as those who chose to move to other provinces to be with their relatives.

It is important for the media and military to establish the protocols for special briefings and for embedding of journalists with military units. A military-media panel should establish standard principles on security issues and other protocos for coverage to observe both safety and operational security.

MARAWI AS A COMMUNITY AND SOCIETY

War is more than just the fighting. War disrupts lives. It breaks up communities. It involves conflict among citizens and members of the same society.

To report war in-depth, journalists must try to learn as much about the community. Journalists must appreciate the history and geography of a place because these provide leads into aspects of culture, which may make possible a greater understanding of the conflict.

Recommendation:

Media training and preparation must include a thorough grounding on the geographical landscape, the history and significance of the place. A better understanding of the Maranaos, their place in the landscape of Mindanao, as well the Christians of Marawi would have added depth to coverage of the war.

A greater familiarity with the facts and history of the affected community eases the rapport of reporter with sources and can open up more opportunities to get out of the box of the military conduct of war.

Like government, civil society groups must acquire the confidence in dealing with the press as this connection enhances the advocacy of any group. Information management skills training should be included in the organizational framework, with members who are able to take turns speaking to the media, articulating the perspective that may be missed in news accounts concentrated on official sources.

MAUTE AND THE ISIS CONNECTION

Was the ISIS connection real? Were there foreign agents working with the Mautes? Did the deaths of the Mautes put an end to foreign terrorist threat?

Conflict plants seeds for more conflict. The awareness of the issues which led to the breakdown of peace and stability in Marawi must be raised so each member of society sees more clearly the issues as a stakeholder.

The news did not seem to carry much news about whether or not there was an ISIS connection, as government began to use the term, ISIS-inspired.

Media coverage must include an agenda for peace, identifying the voices involved in the search for peace, involving the community themselves in the quest for peace.

Recommendation:

While the international media reported Marawi as possibly opening of a new ISIS arena in Mindanao, local media did not report on this except as cited by the military. Even with the end of the siege, this issue needs to be subject to journalistic inquiry.

Media should pick up the issue threads which were made more obvious in Marawi.

The question of the ISIS connection and affiliation requires follow up, as Filipinos need to be aware of such threats.

Concerned agencies, but perhaps, more important, experts and the academe should build up knowledge that will sustain the formation of a sound policy for dealing with the threat.

RECOVERY AND REBUILDING

The aftermath of war poses a different kind of challenge to the media. What narrative threads should be picked up about recovery and rebuilding? Reports are often focused only on statements made about the cost of rebuilding and how the government is sourcing these funds, mostly about China and Chinese businesses providing the necessary funding. Such official complacency is cold comfort for r the residents themselves who have lost the place of their birth, their homes and their communities.

Manila-based and Manila-oriented agencies and sources have been heard. But what about the people who must return and pick up their lives in the ruins of Marawi?

uy

uy

Recommendation:

NGOs, CSOs in TFBM should be part of the news agenda as media focuses on the rehabilitation and rebuilding of Marawi.

Dealing with the missing and the dead remains a heavy burden for the people of Marawi. Media attention will provoke more action on the part of agencies who are assisting families who have lost their members.

Conclusion:

The siege of Marawi reflects the same longstanding blind spots that media has had in covering Moros and Mindanao. So many Filipinos cannot think of either Moros or Mindanao unless it is in terms of trouble, the source of conflict, because such news has defined the identity of the people and the place.

So many Filipinos are unable to appreciate the historic grievance that had given rise to so much disenchantment and estrangement among the Bangsamoro. There is little appreciation for what it is like to be discriminated against, to be treated as second class. Few are able to recognize the legitimacy of the Moro aspiration to be recognized as Filipino and valued for their difference.

The lack of national support for the idea of an autonomous Bangsamoro region as an integral part of the Philippines has prevented the peace process from reaching a satisfactory settlement.

Reporting on Mindanao is triggered mostly by problematic issues, the outbreak of violence and fighting. This must stop. Coverage of Mindanao must reflect its geographic importance, its ethnic richness, and the rich diversity of its population.

The media must overcome the difficulties of reporting on Mindanao and the Moros. They must learn to report and report regularly, even when there is no conflict, controversy and war.

Without this conscious effort to build up Mindanao news, there will be no genuine national coverage by the national press.

Leave a Reply