The perniciousness of political violence

POLITICALLY MOTIVATED killings easily grab headlines. In the Philippines, these have been disturbingly frequent. The assassination of Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo – so far one of the biggest stories in 2023 — proves this. While the coverage of the killing has explored different angles as it tracked the unfolding of key developments, the news has also called attention to the impunity of these attacks, highlighting its persistence in local politics.

It’s not just Degamo. News reports have recorded numerous other local officials as victims of what appear to be politically motivated attacks, most of which have occurred at the barangay level.

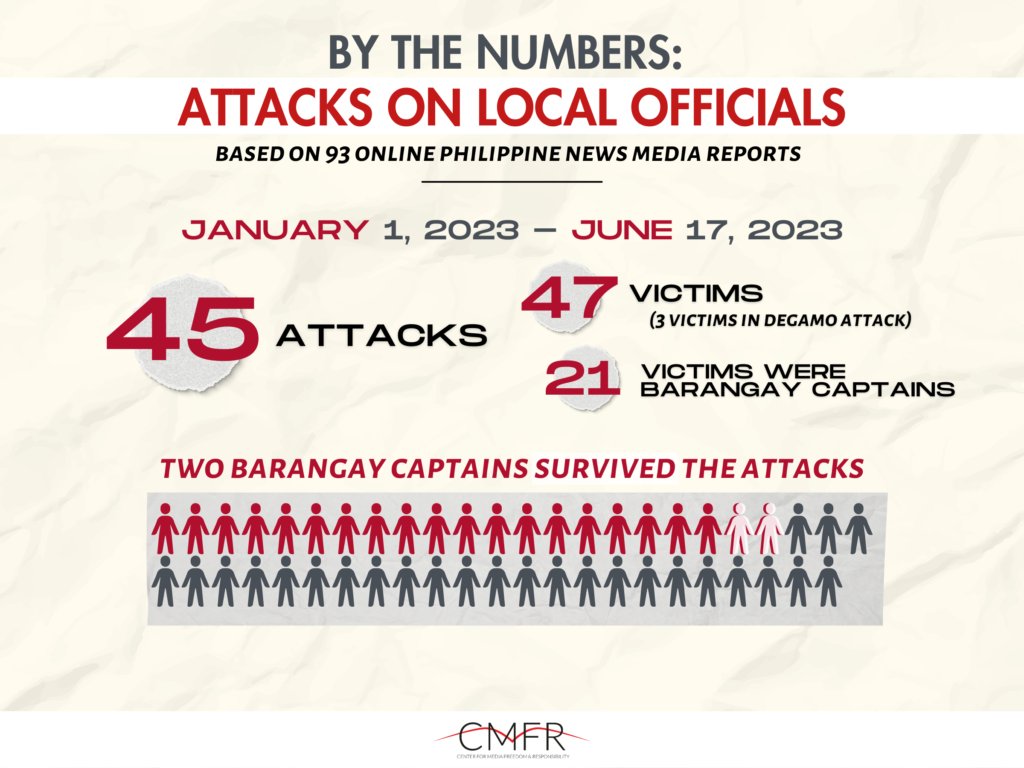

CMFR reviewed and analyzed news reports on attacks against local officials published online from January 1 to June 17, 2023; and found a total of 93 online reports on 45 separate attacks, using a search engine keyword. The search counted a total of 47 victims. The attack on the Degamo residence on March 4 recorded the highest casualty count of local officials in a single incident. the governor and two barangay officials, along with seven civilians. Aside from the governor, two barangay officials and seven civilians also died, bringing the “Pamplona Massacre” death toll to ten. The extensive news coverage and follow-up on the Degamo case is an exception to the usual news treatment of attacks against local officials, done mostly as piecemeal breaking news.

The brazenness of the attack, which took place in broad daylight, the number of victims, and Degamo’s position as provincial governor certainly contributed to the newsworthiness of the incident. In sharp contrast, the killings of barangay officials in different places were reported as separate incidents, with hardly any follow-up reports.

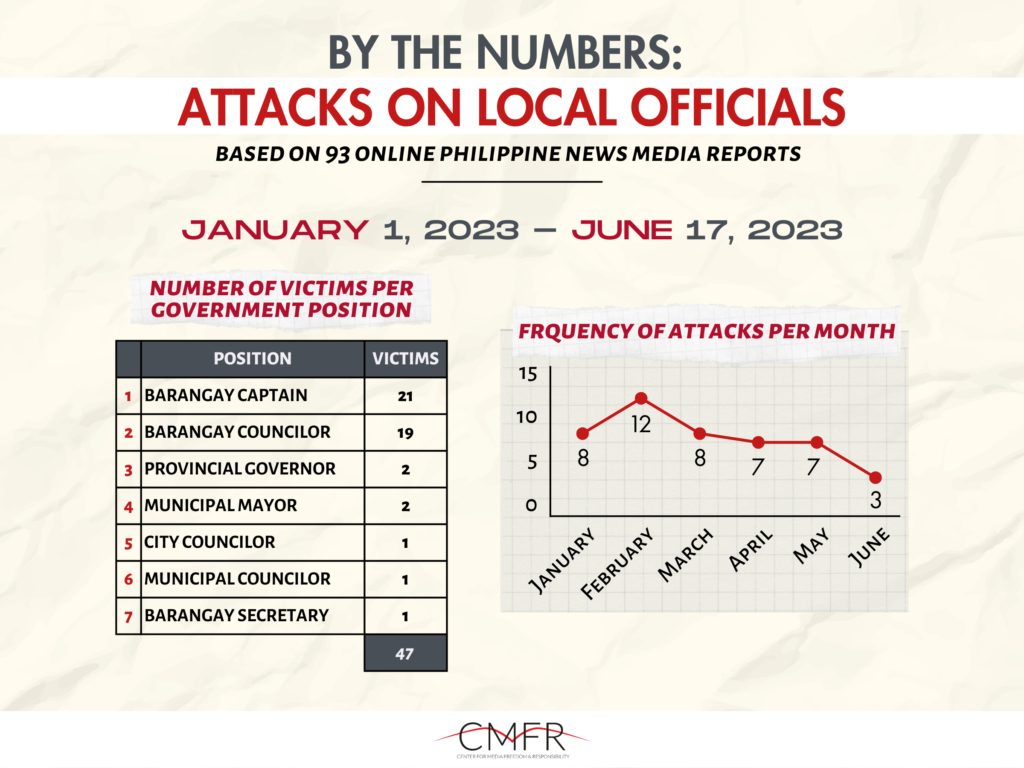

Apart from barangay captains, 19 victims were barangay councilors and seven were local officials occupying other local government positions at the barangay, municipal, city, and provincial levels.

The monthly frequency of the attacks was higher earlier in the year, with the peak occurring in February with 12 attacks, an increase from eight attacks in January. In March, the frequency dipped back again to eight, then seven in April and May. As of June 17, media reported three attacks on local officials.

Pattern of Killings, Local Elections

Some media, namely the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inquirer.net, Rappler and the Philippine Star, correctly noted in reports and editorials the pattern of electoral violence as connected to the upcoming barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan elections in October.

Key highlights of these reports:

- Using the findings of a first of its kind quantitative study on political killings in the Philippines from 2006 to 2021, Inquirer.net’s March 6 in-depth report contextualized the “string of attacks” that culminated in Degamo’s killing. An interview with political scientist Maria Ela Atienza provided additional analysis and insight to the background piece. In a separate April 17 report, Inquirer.net also presented data on the attacks on local officials in Negros Oriental since 2016.

- Rappler’s report listed incumbent and former officials killed under the Marcos administration. First published on March 4 and last updated following the April 9 killing of a Maguindanao barangay councilor, the article documented case details and linked points found in media coverage.

- The Philippine Star’s reports on March 16 and April 11, while not as detailed and context-rich, consistently connected the killings to local elections and provided a broad perspective by recounting previous cases to illustrate the pattern of the attacks.

Other media merely deferred to official statements and echoed police reports as their sole sources. Out of the total 93 reports comprising the data set, 72 or 77 percent relied solely on police sources. Most reports stuck to the crime story angle and were limited to the particulars of the investigation, without even mentioning the upcoming local elections. This treatment sidelined the greater implications of these attacks on the culture of political and electoral violence.

Electoral Violence

A March 14 GMA News Online report on the killing of two barangay captains in separate gun attacks in Cebu and Maguindanao noted the Philippine National Police (PNP) spokesperson in Cebu saying that PNP policy does not consider these killings as “election-related” because the “poll period has not yet started.”

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) has set the official election period from August 28 until November 29. The PNP is tasked by Comelec to monitor, track, and investigate incidents of election-related violence.

The PNP’s classification, needless to say, tends to serve the police’s own purposes, whatever they may be; but the view does little to provide insight into the prevalence of political violence.

Media should, therefore, make the connection on their own– that violence against local officials occurring outside of the election period can qualify as electoral violence. Journalists can do it by improving initial coverage of the attacks and follow-up on the continuing investigation. Newsrooms should remain alert to the typical rise in attacks as the local elections approach.

Political Violence

But more broadly, the news media should look at electoral violence as part of the larger and pernicious culture of Philippine politics. Violence breaks out, even during a lull in election activities because politicians, particularly political dynasties, are possessed with the power and the means to eliminate rivals and competitors. These have consolidated their power for so long that they can resort to violence with impunity.

Such violence takes its toll on human lives. But it also endangers democracy. Politically motivated, often deadly, violence narrows public participation in the electoral process and in the whole democratic project itself. It keeps power concentrated among politicians and within political clans who have no qualms wielding violence as a weapon against their opponents, against dissenters, and even the public.

The news media ought to keep this context in mind as they report on the forthcoming campaign and elections, navigating the danger zones and hot spots of Philippine politics.

Leave a Reply