Marcos follows Duterte’s model of disinformation

Second of two parts

NOT SURPRISINGLY, Rodrigo Duterte’s successor, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., has followed the model set before him. The goal of the Marcos return to power was stated clearly by Presidential sister and Senator, Imelda “Imee” Marcos: “What’s most important to us is, of course, our name, the family name… The legacy of my father is what we hope will be clarified at last.”

As in Duterte’s bid for the presidency, a savvy campaign using online political disinformation has been credited for Marcos’ electoral triumph in May 2022.

A November 2022 CMFR monitor described how the disinformation networks were mobilized over the years to rehabilitate the Marcos image and enable his victory: “The Marcos family has capitalized on these networks to gain public sympathy, pushing the narrative that they were victims of the People Power uprising in 1986 and had been wrongfully punished by the government since.”

In the days leading up to the elections and following his win, news accounts noted the impact of disinformation on the May 2022 elections, particularly its influence on Marcos’ electoral triumph.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) interviewed academic Jonathan Ong, who identified “historical revisionism” as the core narrative in the May 2022 elections. He added that disinformation narratives “pushed by supporters of Marcos” in particular “shaped” the elections.

VERA Files, in their extensive fact-checking of election-related claims for the 2022 election period, found that disinformation circulating online benefited Marcos the most and certainly factored into his victory. Among the presidential candidates, Marcos was the “top beneficiary of election-related disinformation.”

Rappler, for its part, tracked “the many ways propaganda and disinformation related to the Marcoses thrive on social media, how platforms either respond or allow it to happen, and how the Marcos family benefits from the lies and manipulation.”

Meanwhile the public has become more aware about disinformation or “fake news,” as noted by public opinion surveys.

A December 2021 survey by Social Weather Stations (SWS) showed that 69% of respondents believe “the problem of fake news in media like television, radio, and newspaper is serious.” In October 2022, a Pulse Asia survey showed that “nine out of ten Filipino adults or 86% said “fake news” is a problem.” A CMFR report noted how media covered the survey results.

While leaving other urgent issues unattended, the Marcos administration seems set on addressing the problem of disinformation.

On March 8, Cherbett Karen Maralit, Presidential Communications Office (PCO) Undersecretary, issued a statement outlining plans for a national media and information literacy campaign aiming to combat disinformation. The campaign will start with a study to identify “reliable and credible sources of information” and “profiles of misinformation and disinformation peddlers.” Maralit said the study would produce results by mid-2023 and that by the end of the year, the government will hold a “Media Literacy Summit” event where stakeholders hopefully “commit to the cause.”

Media picked up the announcement but were stuck in simply recording the particulars presented by the spokesperson. Only ANC, VERA Files, and “Facts First” broke through the surface of these details to dip into the issue.

On ANC’s Rundown, anchor Nikki de Guzman interviewed Jonathan de Santos, chairperson of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP). The two discussed media consumption habits, information sources, the involvement of other stakeholders in the government’s program, and the methods which could make the program more effective.

Only Christian Esguerra took up the prickly but crucial question: “Does the Marcos administration have the credibility to lead a media literacy and anti-disinformation campaign?”

He discussed the issue on his podcast Facts First on March 13 and in a commentary for VERA Files.

In his video commentary for VERA Files, Esguerra questioned the capacity of the Marcos government to counter disinformation because the Marcos campaign had openly used propaganda based on a false presentation of the past, referring to the continuing claim that the Martial Law period was a benevolent passage.

Esguerra’s podcast discussed the same issue with three guests who all expressed reservations about the government’s effort.

The discussion took up issues of transparency, participation, and objectives, with clear agreement on the main point: the administration’s lack of credibility in undertaking a campaign on disinformation, given its own use of false propaganda. Discussion also expressed doubts about how the President’s office could teach critical thinking or designate sources of valid information.

They flagged the possibility that the government program could stifle criticism and move toward censorship; that the effort could go hand-in-hand with Congress passing laws against “fake news,” a slippery slope that would further weaken press freedom in the country.

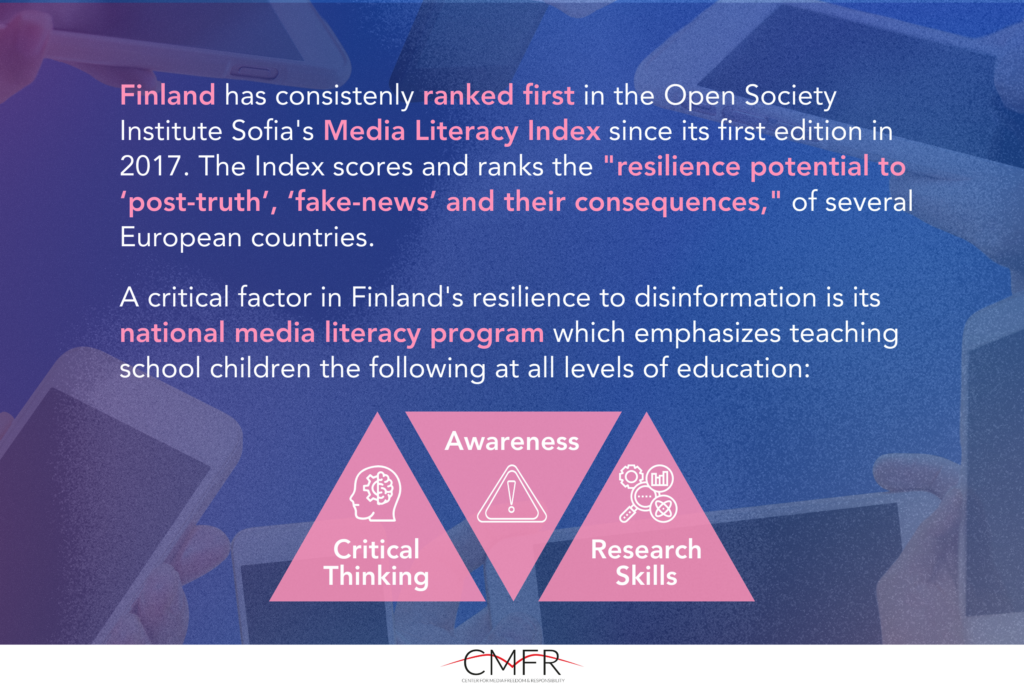

Esguerra and his interviewees agreed that any process must involve a “whole of society” approach; suggesting that the campaign’s implementers learn from Finland where efforts integrated critical thinking and media and information literacy as early as possible in basic education.

Finland’s whole-of-society approach

Out of over 40 European countries, Finland was found to be the “most resistant to fake news.” Resistance to disinformation is taught to children as early as kindergarten by “embedding” media and information literacy and critical thinking in its national curriculum early on. Students learn about methods used to deceive social media users: half-truths, manipulated images, videos, and audio, bots, deepfakes, and false profiles.

Juha Pyykkö, Finland’s ambassador to the Philippines, explained Finland’s “whole of society approach” to Inquirer.net: “The whole society—government, business, civil society, academia, all of them, they get together, and they design the policies, and they decide the call to action. It’s not enough that the government only would be acting on it.”

Conclusion

The plan of the Marcos government to lead a campaign, should it proceed, should not be left without critique or comment. There are enough Filipinos concerned about the disease of disinformation that has infected the entire society, and at the core, its politics.

Journalists should do what they can to share what is already known about the phenomenon, its conduct and how government is part of its spread.

This much has been established: Politicians including presidential candidates, have gulled enough voters to believe lies and win elections on this basis. Taking office, these and their masters of propaganda continue to perpetrate falsehoods, controlling and manipulating how and how much people think.

If enough people know, maybe, it may not be too late to save “patient zero.”

ALSO SEE: “Part 1: Government ’s role in the spread of disinformation“

Leave a Reply