Racing against Crises: DOH, DA still headless

Last of two parts: Absentee DA secretary

AGRICULTURE COULD not be more of a gut issue, with food being the most basic of goods and the threat of a food crisis on the horizon.

However, by taking on the agriculture portfolio as a concurrent responsibility, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. set up both consumers and farmers to receive only his divided, if not entirely distracted attention.

The pandemic as well as a chain of disasters caused disruptions in the food supply chains that have added to inflation caused by global events. These are purely local issues which should have been addressed by government. As the Duterte administration failed to work on sustaining crop production and distribution, the new Marcos government has also been completely laid back in addressing possible food shortages.

CMFR presents a two-part report, Part 1 discussed the problems on the health front. Part 2 reviews the coverage of agricultural issues that have been left to a department without a full-time Secretary. It highlights key points in the performance of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as Agriculture Secretary.

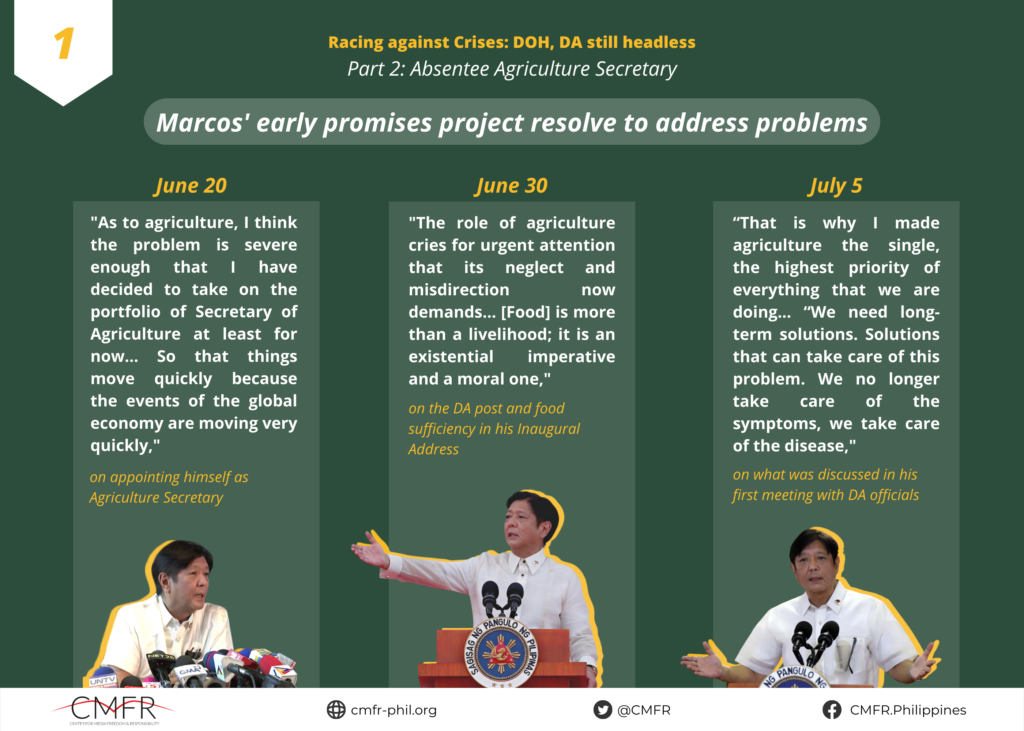

Early promises project resolve

Marcos Jr.’s resolve to be concurrent Secretary of Agriculture to “quickly” address longstanding problems of agriculture was a dubious decision that raised eyebrows. He announced this on June 20, ten days before his inauguration. He justified taking the post “for now” by citing the “severity” of the DA’s problems. To Marcos, these needed the Chief Executive’s attention – without any mention of how the President’s attention is called to other concerns from day to day.

As far as his words go, Marcos appreciates the paramount importance of agriculture in the national economy. In his inaugural address on June 30, he expanded on his campaign promise to give agriculture and its related concerns high priority: “The role of agriculture cries for urgent attention that its neglect and misdirection now demands.” In the same address, he added that agriculture is “more than a livelihood,” it is an “existential” and “moral” imperative.

On July 5, shortly after he took office, he again vowed to make agriculture a “top priority” and to “cure” the sector’s problems following his first meeting with DA officials.

In those early days, Marcos’ words showed promise. But farmers were skeptical, immediately pointing to his lack of experience and qualification for the post. It did not take long for Marcos himself to prove his critics correct after some policy missteps, as shown in the succeeding graphs.

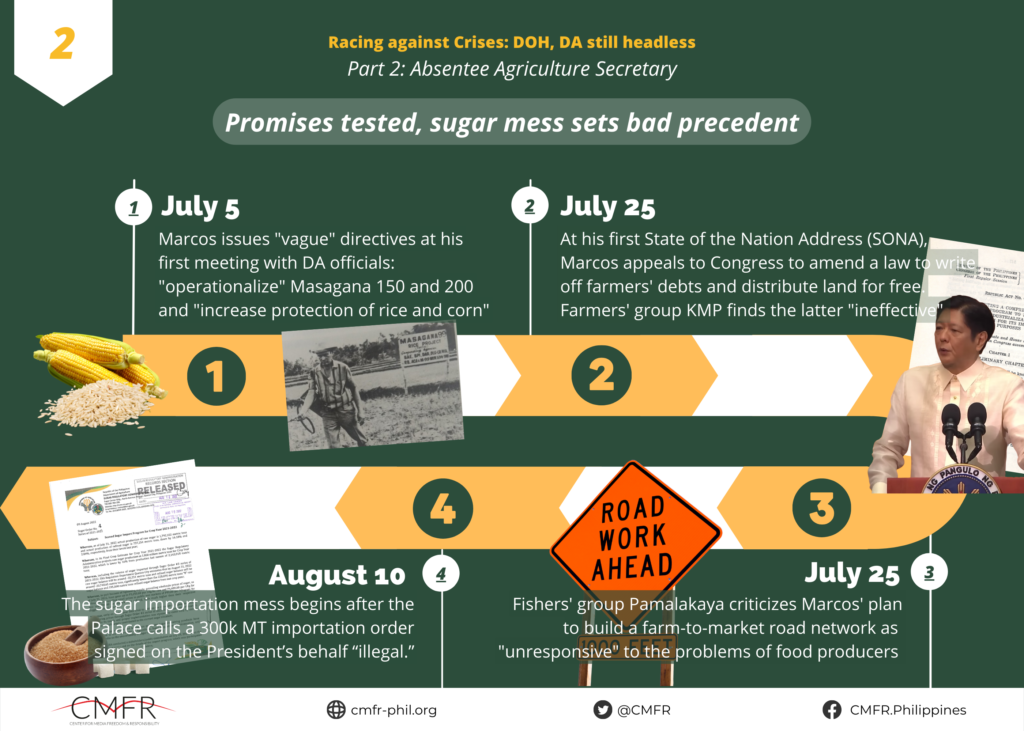

Promises put to the test

The following timeline illustrates how the President and concurrent Agriculture Secretary has only himself to blame for the DA’s mess of problems:

Marcos’ meeting with DA officials on July 5 also saw the Secretary eyeing the revival of a program first implemented by his father: “Masagana 150, Masagana 200, these are good plans that we have to put into place, let’s operationalize them already.” William Dar, the previous administration’s DA chief proposed the programs named after Marcos Sr.’s Masagana 99. Rappler noted that the older Marcos’ program “left rural banks bankrupt and smallholder farmers in debt.” The report also noted that Marcos also wanted to “increase protection of rice and corn,” a directive they called “more vague” than his directive on Masagana 150 and 200.

In his State of the Nation Address on July 25, the President highlighted food self-sufficiency, agrarian reform, and land distribution as targets for policy action. Marcos called on Congress to amend the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law of 1988 to condone debts of agrarian reform beneficiaries. He added that still-undistributed land would be given for free.

While the move to write-off farmers’ debts was welcomed as long overdue, Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP), a progressive farmers’ group, found the free land distribution to be “ineffective at best and duplicitous at worst.” The policy failed to implement land conversion, and the land reform program did not improve the lives of farmers, most of whom remained poor despite their ownership of land. KMP said, Marcos is only making it easier for private entities to take advantage of poor farmers, who would sell their land to developers for quick cash or could easily fall victim to landgrabbers.

Marcos’ farm-to-market road network plan was also criticized as being “unresponsive to the issue of rising costs of agricultural production” by fishers group Pambansang Lakas ng Kilusang Mamamalakaya ng Pilipinas (Pamalakaya).

Sugar mess blame game sends bad message

The second graph also notes that the sugar importation mess which began on August 10 was the first issue to test the executive capacity of the new administration. The Palace’s immediate reaction to the controversial Sugar Order No. 4 came in the form of a threat: “heads will roll.” Malacañang called the order to import 300,000 metric tons of sugar signed on Marcos’ behalf “illegal.” The order was meant to address an impending shortage. The confusion from within was obvious, as suspensions, resignations, and a Senate probe followed. All this despite Marcos’ initial openness to the plan and later allowing importation to proceed anyway. But a respected career official ended up as a casualty, making himself solely accountable for the policy decision to import sugar.

A Philippine Daily Inquirer editorial explained further how this set a bad precedent: “This disregard for a fellow official left on his own to make a tough decision would scare away highly qualified candidates for the job.” Clearly, the President has too many other issues to attend to and should look for someone who can do the job at the DA full time. An editorial from the Philippine Star noted that the sugar mess raised questions on the “quality of management in the new administration.”

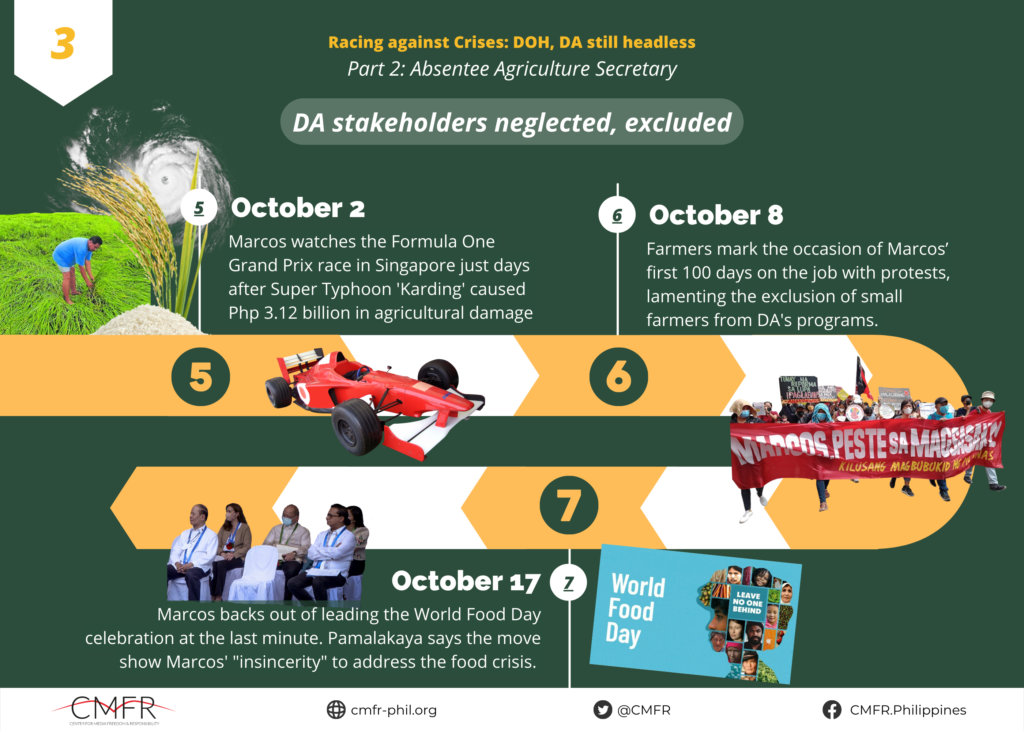

DA stakeholders neglected, excluded

Marcos’ backing out of the leading World Food Day celebration at the last minute presents evidence of Marcos’ neglect, in the aftermath of Super Typhoon ‘Karding’ (internationally called ‘Noru’) which battered Luzon on September 25. It was revealed that just days after ‘Karding’s’ onslaught, Marcos flew off to Singapore to watch the Formula One Grand Prix race on October 2. Farmers hit Marcos’ getaway and “lavish lifestyle”, which they called “callous and insensitive” given that farmers were “still reeling” from the effects of the typhoon at the time. Prior to flying to Singapore, Marcos commented that the country “may have gotten lucky at this time” despite the Php 3.12 billion in agricultural damage and lives lost due to the disaster.

Farmers marked the occasion of Marcos’ first 100 days on the job with protests on October 8. Leonardo Montemayor, Federation of Free Farmers leader, called attention to the greater neglect of small farmers, lamenting the exclusion of smallholder farmers in the DA’s programs. He said that within the first hundred days of the President-Secretary’s term, smallholder farmers were being sidelined in favor of big businesses involved in agriculture. Montemayor noted that the Secretary had never directly consulted farmers. Roy Kempis, retired agriculture professor, likewise agreed that the DA’s preference for “organized” farmers resulted in missed opportunities and inequalities.

Marcos shirked duties as DA Sec. again on October 17. It was reported that Marcos was absent at the country’s annual celebration of World Food Day due to scheduling conflicts. His non-attendance was announced at the last minute, on the same day of the occasion that Marcos was scheduled to lead.

Pamalakaya slammed his absence at the event. The group told media that Marcos’ absence spoke volumes: “skipping the significant World Food Day event is very telling of him as an agriculture secretary—insincere to address the ongoing food crisis in the country.”

Competent, full-time DA Sec wanted

Marcos’ performance has been met with criticism and calls from farmers, industry experts, and lawmakers to appoint an Agriculture chief. On October 20, at the sidelines of a business event aiming to foster collaboration between policymakers and business leaders, Marcos told reporters that he would keep the agriculture post despite calls from legislators and progressive groups for him to step down. Marcos insisted that his presidential power is key to addressing the DA and its concerned sector’s many problems: “There are things that a president can do that a secretary cannot, especially because the reason that you gave—the problems are so difficult that it will take a president to change and turn it around… I think I’m still needed there,”

The most recent call on October 23, to appoint a “full-time, hardworking” DA chief, came from farmers in reaction to Marcos’ insistence that he remain at the post. This is shown in contrast in the visual.

The President’s promises made when he announced he would take the agriculture portfolio months ago remained to be just that—promises. As such, it is necessary that the media highlight the need for a full-fledged DA secretary.

Given Marcos’ insistence on staying as DA Secretary and a food crisis on the horizon, demanding accountability for Marcos’ unfulfilled promises could not be more important. Media’s reports dwelled on the existence of problems linked to food and agriculture but could have been sharper in calling attention to the Secretary’s lack of involvement in addressing these, as shown by his lackluster performance so far.

Also see, “First of two parts: DOH still has no secretary“

Leave a Reply