Accrediting vloggers: Free press advocates question intent

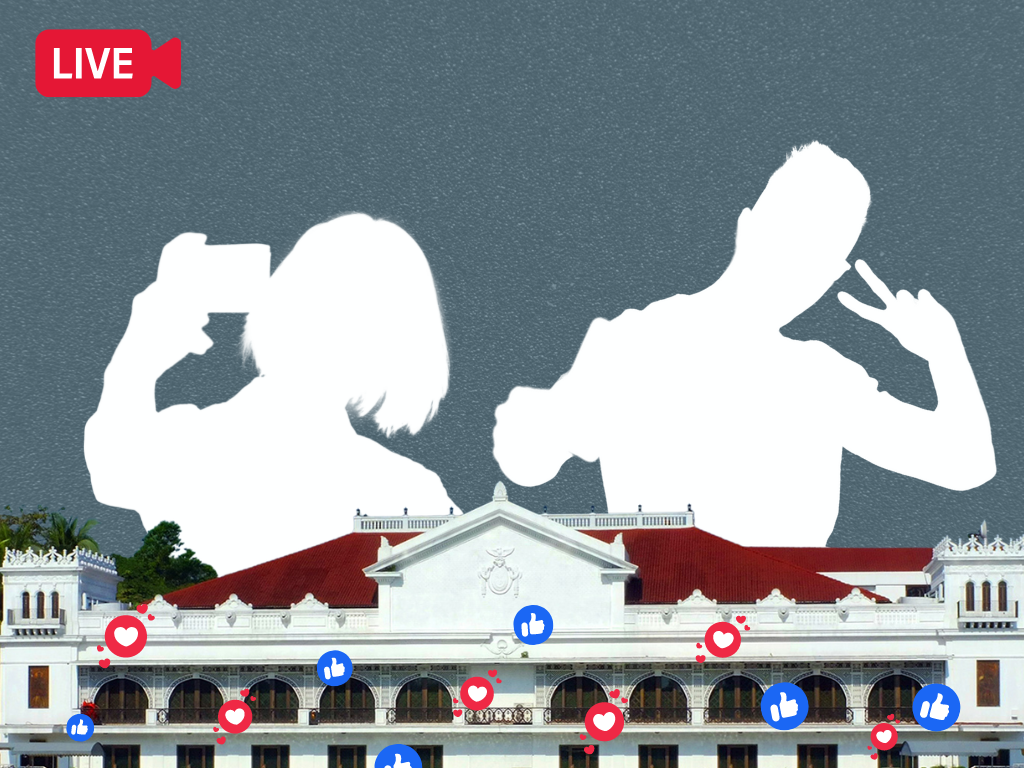

THE PLAN to accredit vloggers (video-bloggers) has doubled concerns over the incoming administration’s regard for press freedom.

On June 1, incoming press secretary Trixie Cruz-Angeles announced that she will prioritize granting vloggers access to Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr’s press briefings. A known content creator, Cruz-Angeles herself has been publicly supportive of both the president-elect and President Rodrigo Duterte.

Cautioning against the move, press freedom advocates recalled the actions of partisan vloggers, who peddled dubious claims to boost the Marcos campaign. The proposal has also ignited debate over whether bloggers can reliably produce journalistic work.

It is urgent to note that the Constitution protects the citizen right to know. Given the Marcos camp’s history of avoiding and antagonizing critical media, it is equally important to scrutinize the intent and the process by which vloggers will be given access.

Engaging the citizenry

Since 2010, the government has been hearing proposals to widen media access to include bloggers as a means of citizen engagement. Blogger lack of accountability, for one, has been argued against their accreditation.

During the presidency of Benigno Aquino III, officials studied the idea of accrediting bloggers to cover the Palace. Former presidential spokesman Edwin Lacierda favored the proposal, eager to welcome voices from across the political spectrum. The idea was eventually scrapped over the Malacanang Press Corps’ objections. Speaking to ANC in 2017 about the decision, Lacierda cited concerns over bloggers’ lack of uniform editorial standards.

The Duterte government also floated the idea, citing social media’s supposed effectiveness in delivering information to the public.

In 2017, outgoing press secretary Martin Andanar signed Department Order 15, the Interim Social Media Practitioner Accreditation. Former Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) assistant secretary Mocha Uson advocated the policy, but it was never implemented due to her “inaction.”

PCOO justified the policy then as a way of engaging the citizenry and “enriching” the quality of discourse.

The order defined blogging practitioners as those who maintain “publicly-accessible social media pages, blogs, or websites which generate content and whose principal advocacy is the regular dissemination of original news and/or opinion of interest. ” The order required applicants for accreditation to be eighteen years of age, and to have at least five thousand followers on their chosen digital platform.

On June 10, 2022, Cruz-Angeles said her office will assess existing PCOO policies including Department Order 15, and decide if it is the “right time” to include vloggers in official engagements. Angeles has declared that the incoming government will not “ignore” social media as a way of delivering information.

The push is not out of step with legal principles. The public’s right to know is protected under the 1987 Constitution; specifically, Article III, Section 7 states, “The right of the people to information on matters of public concern shall be recognized.”

Still, the spread of dubious claims from partisan creators requires scrutiny into those poised to share space with professional journalists.

CMFR trustee Vergel Santos on ANC underlined the perceived difference between journalists and content creators. Journalism, through layers of checks on output, is a “piloted train;” bloggers are individual operators who self-publish, and are given more to inaccuracy, Santos said.

Bloggers have long since argued for their role as “citizens’ watchdogs” who cover stories unfollowed by big media.

Noemi Dado, a local blogger, took exception to what she described as a “blanket statement” from Santos, writing in a June 5 post: “Not all bloggers are the same just as some journalists are not always credible.”

In the same blog, Dado maintained her adherence to editorial standards. “I don’t know with the other bloggers especially those that covered Marcos Jr during the campaign, but I set my own journalistic standards and ethics.” Dado then urged the new leadership to deliberate on “ethical standards” prior to vloggers’ accreditation.

Dado is co-founder of non-partisan group BlogWatch, which in 2010 was accredited by the Commission on Elections to cover poll-related activities. In 2015, a report by Dado and fellow blogger Jane Uymatiao was recognized as “Best Story” during the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism’s Data Journalism PH event.

Cruz-Angeles for her part has not said much about the need for integrity among would-be vlogger-reporters. She instead told the media that social media engagements, which measures likes, shares, and comments on digital platforms, will be among the criteria in accrediting vloggers.

Payback for support? Critics question motive

Columnist and blogger Tonyo Cruz, in a June 11 Manila Bulletin piece, questioned the proposed method of selection, pointing out that high engagements could be misleading.

“Is the next administration looking only for vloggers whose social media engagement consistently amplifies, elevates, cheers, or supports Marcos? What if a vlogger has both high following and engagement numbers, but the overall reaction to Marcos is negative?” Cruz wrote.

Cruz further called attention to the redundancy of vloggers covering the president. For one, Angeles and Marcos run already popular blogs on Facebook and YouTube respectively. On top of this, they will be given the arsenal of state media, which includes Radio TV Malacanang, PTV4, and Philippine News Agency, Cruz wrote.

Meanwhile, for journalist Joel Pablo Salud, backlash to the decision has not been totally warranted.

“Aren’t journalists overreacting? Is this because we feel slighted, or not the least insulted, by PCOO’s choice of vloggers over well-trained newshounds,” Salud wrote in Philippine Star Life. He also pressed journalists to respond by learning to use social media more effectively, instead of prying access away from vloggers.

Nevertheless, advocates and groups have continued to air their misgivings over Angeles’ proposal.

On June 2, University of the Philippines (UP) journalism professor Danilo Arao said that the PCOO must promise impartial treatment and publicize guidelines on accreditation. He warned against the PCOO chief’s merely “paying back” vloggers who boosted Marcos Jr.’s campaign on digital platforms.

NUJP for its part raised questions about accountability. “Will the PCOO, which will essentially vouch for the vloggers and influencers it accredits, also be accountable for the content that they might release? Would vlogger access be dependent on whether the content is favorable to the incoming administration or not,” the group asked in their June 2 statement.

Diosa Labiste, also a UP journalism professor, stressed on June 16 the “democratic responsibility” embedded in the coverage of leaders. This would require vloggers to declare any conflicts of interest, and to adhere to the same set of ethical standards by which journalists operate.

Media themselves must raise these questions to the incoming leadership. Journalists should insist on the integrity and transparency of the accreditation process.

Leave a Reply