Ozamiz Raid: Of Regularity and Irregularities

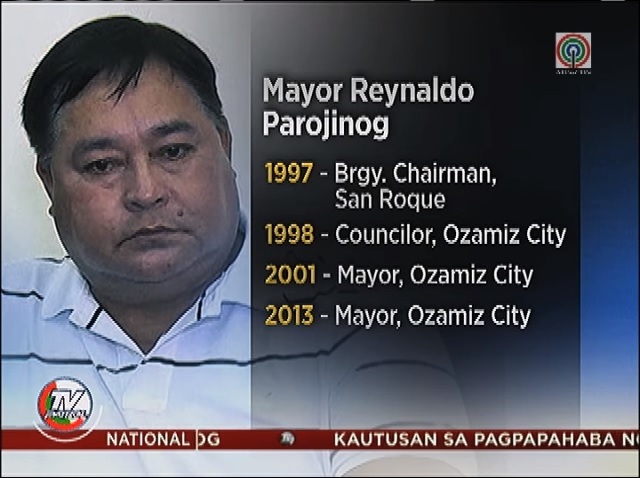

Screengrab from TV Patrol.

PRESIDENT RODRIGO Duterte just crossed out another name in his narco-politicians’ list with the bloody raid on the residential compound of Ozamiz City Mayor Reynaldo Parojinog Sr.The attack left 15 people dead, including the mayor, his wife, brother, nephew, members of his household and security guards. Parojinog was the third mayor in the President’s list to be killed by the police.

The record on police reports say that on July 30, at around 2:30 a.m, combined elements of the Regional Criminal Investigation and Detection Group, Misamis Occidental Regional Police and Ozamiz City Police went to the mayor’s residence with a search warrant to check the premises for illegal firearms. They were “met by a volley of fire,” forcing the authorities to retaliate.

In the same operation, the police arrested the mayor’s daughter, Vice Mayor Nova Princess Parojinog, whose name was included in the president’s list, and his son, Councilor Reynaldo Parojinog Jr. Both are now at detained in Camp Crame.

CMFR monitored major broadsheets Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star and Manila Bulletin as well as TV prime time newscasts TV Patrol, 24 Oras, Aksyon and News Night from July 30 to August 3 to check how reports on the raid reflected the issue of human rights.

Looking into Irregularities

The Parojinog family had been associated with the Kuratong Baleleng group in the 1980s. Octavio Parojinog, father of the slain mayor, headed the paramilitary organization used by the military to quell the communist insurgency in Western Mindanao. The Kuratong shifted to criminal activities and became notorious for robbery, extortion and kidnap for ransom. After Octavio died in 1990, his sons ran for local office and won, and the family gained a strong foothold in Mindanao local politics.

For some, the Parojinogs had it coming. But the circumstances that led to the bloody encounter have given cause for alarm, raising suspicions about the real intent of the operating team.

Initial reports on TV on the same day of the operation relied mostly on the police as a source. Reporters asked questions about irregularities in the operation: the time the warrant was served, as well as the police action to “paralyze” the CCTVs inside the Parojinog’s compound.

Media reports noted similarities in the raid in Ozamiz to that in Albuera, Leyte; which left another alleged narco-official, Mayor Rolando Espinosa Sr, dead in his jail cell.In both cases, the police served warrants at pre-dawn and claimed that the victims exchanged fire with the police.

Print and TV reports on July 31, explored these issues further. Media carried statements from lawmakers and rights groups weighing in with their questions. Minority senators Franklin Drilon and Francis Pangilinanexpressed suspicion about the unholy hour the warrants were served.

ANC’s Headstart on July 31 interviewed Sen. Francis Escudero on the alleged irregularities in the operation. Escudero explained that the PNP manual states that as a general rule, warrants should be served during day time, unless the judge issuing the warrant directs that it can be served anytime—but still under reasonable circumstances. Escudero also said that while the mayor has long been suspected of having drug links, it does not get him a “death warrant.”

Human Rights Watch Deputy Director for Asia Phelim Kine said that skepticism against the police is justified since questionable accounts of authorities on police operations are not new. The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) also reminded the police to comply with the existing rules on arrests and searches. CHR is currently conducting its probe on the Ozamiz raid.

Senator Panfilo Lacson, noted that unlike Espinosa, Parojinog was killed in his house and not in jail. He added, “At this point, I don’t see anything irregular… Whatever the circumstances of the deaths [are], at least this time, the mayor and the others killed were not under detention in a government facility,”Lacson said.

Presumption of Regularity?

Speaking in a press conference on behalf of the Palace, Senior Deputy Executive Secretary Menardo Guevarra said the government presumes regularity in the conduct of the police in the Ozamiz raid. According to him, those who think otherwise should file complaints so that an investigation can be initiated.

Kabayan party-list Rep. Harry Roque challenged this presumption. An Inquirer, article cited Roque’s statement which said deaths during police operations should be automatically investigated by the Department of Justice through an inquest proceeding to determine if there had been foul play. (“Parojinog case: Presumption of regularity challenged”)

In the same article, Roque cited Chapter 3, Rule 15.4 (Inquest Proceeding Necessary When the Suspect Dies) of the Revised PNP Operational Procedures directing the team leader of the operating unit to immediately submit the incident for inquest to an inquest prosecutor and that the inquest should be done “prior to the removal of the body from the scene” except when the armed confrontation occurs in an area where there is no inquest prosecutor.

No media reports have so far followed up whether the police had concluded an inquest on the deaths of the Parojinogs according to their prescribed procedures.

CMFR had previously cited Atty. Joel Butuyan’s opinion piece in the Inquirer which pointed out that policemen are not granted powers to automatically kill even if the suspect resists arrest (“Duterte’s Drug War: Debunking Presumption of Regularity”), explaining that the “presumption of regularity” does not apply when someone is killed during an operation. Instead, the police are directed by the PNP manual to use reasonable force to subdue and take the suspects into custody and are authorized to use deadly force only when there is imminent danger to human life. In cases of deaths in police operations, the Supreme Court has ruled that imminent danger as a justifying circumstance is not presumed. Thus, policemen who kill a suspect have the burden of proving that the killing was justified.

Improvement in Coverage

CMFR noted how questions of human rights and due process were not reflected in media reporting at the start of Duterte’s drug war in 2016. Previous reports on the drug operations in the last year relied mostly on the police for information. The rights of citizens, including suspects, due process and the rules regulating the conduct of police operations were seldom, if ever, discussed (“Anti-Drug Campaign: Swallowing Everything the Police Says”). Exceptions, such as Inquirer in August 2016 (“Taking a Stand: Journalism for Humanity”), and Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism in November 2016 (“On Espinosa Killing: Media’s Investigative Skills Yield Critical Findings”), were also noted by CMFR.

The coverage of the Ozamiz raid shows improved reference to the human rights context in reporting the drug war. Hopefully, the media will sustain the learning curve.

Leave a Reply