Occupy Pabahay: the Issue of Homelessness

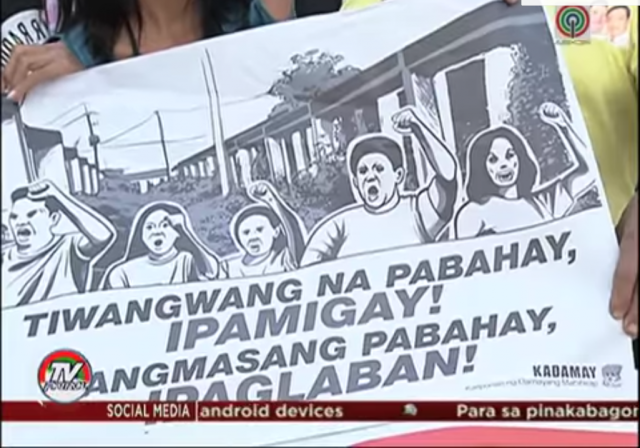

Screengrab from TV Patrol.

HOMELESSNESS IS a global affliction as millions of people and growing communities live without adequate shelter. Although the country has not suffered the pressure of populations seeking refuge, the lack of housing in the Philippines constitutes a crisis in its magnitude.

Not too many knew about Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap (Kadamay) until members of the organization, coming from urban poor communities, occupied around 4,000 houses in government housing projects in Bulacan on March 8. Kadamay argued that the houses were standing empty, while so many people like them live without a roof over their heads.

The National Housing Authority (NHA) decried the occupation of the housing projects, saying that the Kadamay “stole” the houses meant for the policemen and soldiers.

News reported the takeover and the incident forced a serious look at the failure of government to implement even the limited housing projects that the housing agencies had built.

CMFR reviewed the top broadsheets (Philippine Daily Inquirer, The Philippine Star, Manila Bulletin) and top primetime TV newscasts (ABS-CBN 2’s TV Patrol, GMA 7’s 24 Oras, TV5’s Aksyon, CNN Philippines’ Network News) from March 8 to March 31 and assessed the media’s coverage of the issue.

Missing the Big Picture

The media were on the scene almost immediately after Kadamay’s bold occupation. Reports on the scene were carried the same day in TV Patrol. 24 Oras and Aksyon reported it on March 10 while CNN Philippines did so only on March 27. Inquirer published their first story on March 10, Star on March 12, and Bulletin on March 15.

Initial reports were mostly limited to covering the development as an event, focused on the conflict between Kadamay and the NHA. Little was said on the bigger picture of the housing problem outside the Bulacan incident.

According to the NHA, the housing units had been built for personnel of the Philippine National Police (PNP), Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and poor families in Metro Manila living in danger zones. Some of the houses had already been awarded to occupants. The NHA said that it was still in the process of identifying and verifying the qualifications of beneficiaries for most of the houses.

Media captured the exchange of statements, including interviews with the occupants. Other sources included leaders of militant groups, members of Congress, both Senate and the House. These accounts however reduced what was said to mere soundbytes.

A TV Patrol report followed up on the situation of Kadamay occupants after the takeover. The houses were still without power and water connections. Some units lacked toilet bowls, even doors (“NHA, tinaningan ang Kadamay na lisanin ang inaangking pabahay”).

TV and print reports also provided statistics sourced from the NHA, such as numbers of informal settlers in the country and built housing units to demonstrate the gravity of the shortage.

None of the reports delved deeper into the problem. No one went beyond the NHA and the politicians for context and perspective.

It was only in the third week of March that media started to report the takeover as reflective of a policy crisis, the failure of which involves not just one agency of government. It is obvious that incompetence or worse plagues the housing programs but the NHA is not the only one to blame. Housing is too fundamental a need that has to be studied not in isolation, but integrated in how the government approaches the endemic problems posed by population growth, the imbalance of development efforts and the unequal focus of development which results in over-concentration of the urban areas to the detriment of agricultural communities.

Cheer

Inquirer on March 29 did explain why the houses in Bulacan were still standing empty so long after these were built. The NHA built 57,494 houses for policemen, soldiers, firefighters, and jail guards. As of 2015, NHA had only succeeded to get occupants to live in 4,651 houses since the intended beneficiaries among police and soldiers rejected the houses because these were too small, measuring 22 square meters in floor area.

The same report also looked at Commission on Audit (COA) reports which found irregularities, particularly the failure of contractors to submit required documentation. COA, however, has yet to determine the extent of corruption at the NHA (“Takeover shows mass housing woes”).

TV Patrol for its part reviewed the process of identifying beneficiaries for the government’s socialized housing program. It also pointed out that beneficiaries do not apply for the program, but are chosen based on the census of the NHA. Priority beneficiaries are poor families living in danger zones, particularly near waterways that are prone to flooding. However, it is not certain how long beneficiaries have to wait before they can move into the houses (“ALAMIN: Proseso ng pagtukoy sa benepisyaryo ng socialized housing”).

Presidential Intervention

Initially threatening to evict the urban poor group from the Bulacan housing, the NHA through their dialogue with Kadamay, agreed to let the families stay while they undergo screening. The NHA will determine how many of the families are qualified for the government’s housing program. The housing body also notified beneficiaries from the PNP and AFP about the deadline, May 30, for them to claim their units. Unclaimed units would then be transferred to Kadamay.

On April 4, during the 120th anniversary of the Philippine Army in Taguig, President Rodrigo Duterte announced his decision to concede the housing units to Kadamay. Duterte also vowed to provide policemen and soldiers better housing than those in Bulacan.

The presidential decision does not solve the big problem. Currently, the Senate has started an inquiry on the housing problem. Sustained media coverage of the policy and programs for housing will help the search for feasible solutions.

Kadamay is a professional squatters’ association. Their lady leader has been unmasked to have 2 engineer kids and an accountant daughter in Canada.